Hello,

Welcome, new subscribers. Welcome back, old subscribers.

I am revamping this newsletter in the hopes of turning it into a more regular feature of my life and yours. Starting this month, it will publish (at least) monthly. That was my original goal with this thing but I tapered off as other kinds of writing intervened and as I lost sight of this project’s essentially casual and unfussy intentions.

Originally, I had hoped to use this space for notes, unused draft matter, behind-the-scenes scraps of reporting and publishing industry intel, and stuff I liked to read. But somehow, despite my best efforts, I began instead to publish diatribes and ideas about writing—me, a writer who hates and has no ideas! I somehow began writing with an aim toward criticism of media, publishing, and nonfiction tropes—which soon became untenable, since I don’t really have that much to say on those subjects. And when I do, it takes me a while to phrase anything coherently. The pressure to compose a proper essay every month on top of my other work and deadlines meant that I published this letter less and less often.

I’ve been rethinking the uses of a newsletter like this—what I get out of it, what you (hopefully) get out of it—and have come up with a solution. I will never be able to set aside my anxiety and perfectionism enough to publish long essays here regularly, but I can definitely publish news and letters, especially if I divide the newsletter into discrete columns and features and try to keep the whole thing to around 1,000 words. Going forward, I’ll follow a more regular rubric, something like this.

Published: Inside Xinjiang’s Prison State

The raison detritus of this newsletter is to inform you about my work. I will always send out a newsletter when my writing is published.

On Friday, The New Yorker published “Inside Xinjiang’s Prison State,” an immersive interactive feature more than a year in the making which reveals the scope of China's campaign of persecution against ethnic and religious minorities. The story features art by Matt Huynh and photographs by Sam Wolson.

My reporting centers on the story of three men who met while detained inside the same extrajudicial “reëducation” camp in Tacheng, and expands to include many other stories of surveillance, coercion, and forced assimilation across northwestern China. I devote special attention to features of Xinjiang’s security state that in my view have been underreported by other outlets, including live-in Communist Party cadres, forced confessions, and show trials for hundreds of thousands of people from China’s ethnic minority groups.

It’s a project I have spent many months working on with VR director Sam Wolson, artist Matt Huynh (who drew each illustrated frame by hand), animator/technical director Nick Rubin at Dirt Empire, and talented editors and designers at The New Yorker. Part 2 of the project will premiere on March 16 at SXSW as Reeducated, a 360 VR film.

It’s also a heavy web page, with some ambitious design features—including 360-degree animated environments, scroll-based animations and maps, and an audio recording—so I recommend closing your other tabs and giving the page some time to load before scrolling. In the words of newyorker.com's editor, this is the most ambitious immersive visual storytelling The New Yorker has ever undertaken. Like most experiments in narrative and publishing, it has some rough edges. (For what it’s worth, I also found Chrome to offer the best browser experience.)

I will have more to say about the process of reporting and writing this story, bringing it to The New Yorker, and turning it into an immersive feature and VR film, and will plan to dedicate more space to that process in future newsletters. It is the product of more than a year of work and, in a sense, the culmination of several years writing about Xinjiang in various genres and publications, beginning with a Times feature on Kazakhstan and involving, more recently, a 40-page oral history of Xinjiang’s internment drive for The Believer. I have spent a great deal of time since 2018 thinking about how best to approach this subject for an international audience, and the limitations of different genres of nonfiction writing when reporting on distant atrocities in inaccessible places. The solution I came up with here was the result of close collaboration with Sam and Matt, first in Kazakhstan, and later online with collaborators on four continents. I’m extremely proud that this story has made it to a publication like The New Yorker in a form very close to our original vision.

Look for a newsletter later this month where I’ll write more about this project’s long development.

Fugitive World

In this new feature, I’ll stick tidbits from my research and reporting for a book-in-progress about communities in extremis and life in the shadow of the state.

A recent story in Mongabay discusses the history of indigenous resistance to dam projects in northern Luzon. “ ‘The river will bleed red’: Indigenous Filipinos face down dam projects” by Karlston Lapniten gives a thorough overview of contemporary hydroelectric threats to life in the Cordillera. Part of my book focuses on resistance to the original Chico Dam projects in the 1970s and 1980s. Reading Lapniten’s story, I thought back to interviews I’d done in northern Luzon with some of the resistance fighters who came out of the extractive Marcos era: people like Joanna Cariño, a founder of the red-tagged and vilified Cordillera People’s Alliance, the only member of the original executive committee still living. The people living in the Cordillera do not always want what the lowland is selling, whether in peso or USD, and it is Joanna’s lifelong mission to see they are not forced to buy it. The mission gets her into trouble. In 2018, the Duterte government’s Philippine National Police Intelligence Group published a list of all of the known “active terrorists” in the Philippines: a hit list for vigilante death squads. There were 657 names on the list and Joanna Cariño was one of them.

The Mongabay report is dismal. But it reminded me that when I asked Cariño about the yearslong struggle she helped organize against the Chico Dam, ending in an important early victory for the modern indigenous rights movement, she was quick to correct me on my phrasing. “It was not a yearslong struggle,” she said. “It was a decades-long struggle!”

Underread

Next month I’m resurrecting this occasional column as a shorter but more regular feature, one where I advocate for insufficiently adored pieces of nonfiction writing at least one year old. These are true reported works that aspire to longevity or something like it under the host of constraints and compromises all working writers deal with: deadlines, house style, intransigent editors, sudden shifts in consensus reality, and getting scooped, killed, cut, or canned. Stay tuned.

Recommended Reading

In this new column, writers I admire recommend books to me—and you.

A lot of my reading comes by way of personal recommendation. Most of my favorite books were at one time pressed into my hands by a friend or acquaintance. But COVID-19 has meant a dearth of casual conversations at bars and parties where those recommendations usually happen, meaning I’ve been at sea, reading the nutritional text on cereal boxes and the graffiti on the old bottling plant outside my office window. So I’m formalizing the process of rebuilding my reading list by turning it into a guest mini-column.

Our first recommender is Edna Bonhomme, a historian, writer, and interdisciplinary artist based in Berlin. She co-created and hosts the podcast “Decolonization in Action” and writes for many different outlets, including The Nation, Al Jazeera English, and The New Republic. Most recently, she wrote in The Guardian about her experience teaching an epidemic module of a university class that investigated the relationship between fear and public health, connecting the dots between HIV and COVID-19. Edna writes:

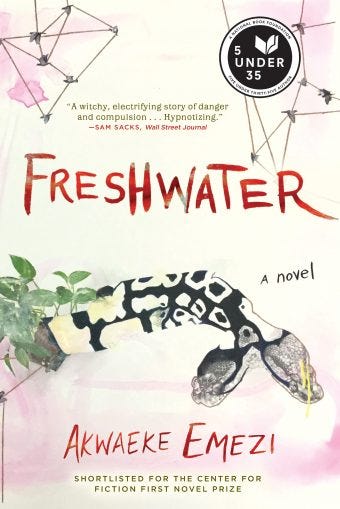

There are two books I’ve read recently that I would recommend. The first is Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi, an Igbo and Tamil writer and video artist. This autobiographical novel explores emotional fragmentation, trauma, and transnational storytelling while also making space for spiritual entities. I was also moved by Anne Boyer’s The Undying.

So was I, Edna! Thanks for the recs.

xoxo

Ben