At the end of Elizabeth Bishop’s “Questions of Travel,” “the traveller takes a notebook, writes.” It is the silent golden hour after a Brazil storm. The traveler is thinking. Was Pascal perhaps wrong about sitting quietly in his room, laptop open, Scrivener pulled up on the screen? Must we leave the house? Take notes? And how? On hotel stationary? A legal pad? A smartphone? A Palm Pilot?

The notebook appears funnily right at the end of Bishop’s poem, unmentioned in the catalogue of observations made in ambivalent defense of the “childishness” of travel, an italicized caboose that trails, while at the same time drawing together, all of the looking and thinking that has preceded it. Yet in life the traveler writes as she moves, usually in alternating bursts or even at the same time, looking and note-taking simultaneously, and anyway to end with notes feels like an odd reversal of a poem’s process of creation. Surely all writing, even for Bishop, begins rather than ends as note-taking, as the gathering of the mind’s lumber into scrawl.

The note-taking is itself the looking. It is itself the thinking, much more so than the act—although the main point is that there is no single, stable act—of writing. For me, half of the “thinking” part of writing something is the jumble of notes that precedes a draft. The second half takes place in revision and editing, meaning that, by the time I sit down to begin (or “begin”) writing, half of the thinking has already happened and the rest of it has yet to occur. All that remains is the horrible, grinding, bootstrapping act of putting down a draft, which brooks no thinking at all. (If I think about it, I’ll never do it.)

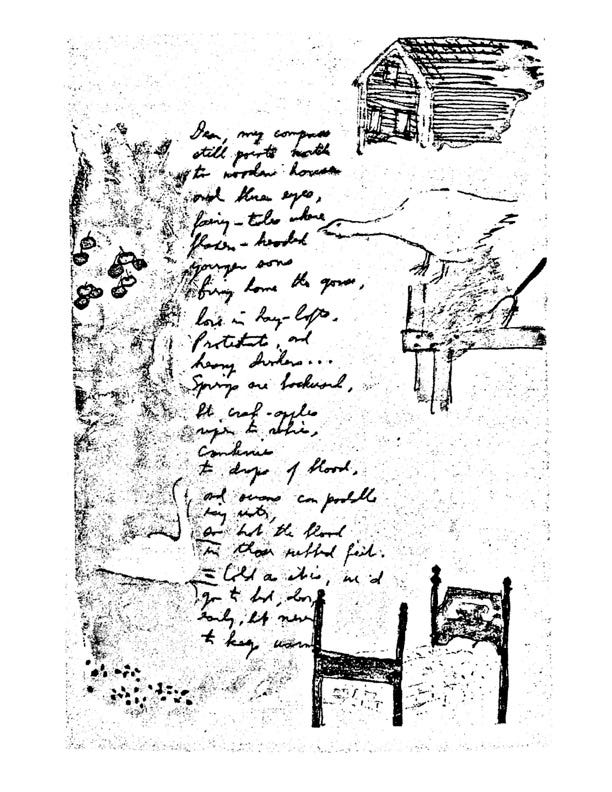

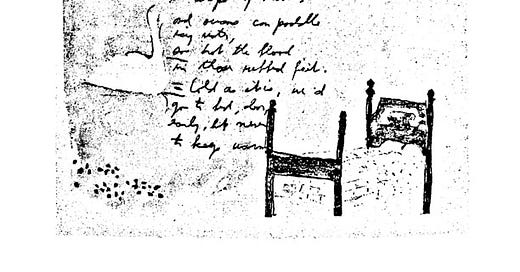

Bishop took notes, wrote drafts—I have taught undergraduates the many drafts of “One Art” that approach the final hard-to-master masterpiece—as all writers do. On a manuscript version of “Dear, my compass” she has drawn apples, a four-post bed, and a goose standing on a table. Elsewhere, there are lines written in a copy of Fannie Farmer’s Boston Cooking School Cook Book. (“Fannie should not be underrated / She has become sophisticated.”) Like a goose standing on a table, the note-taking habits of famous writers inspire fascination and amusement. With some writers—Susan Sontag, prolific diarist, is one—it is hard to imagine that they did not intend or expect their private writing to one day be public, becoming part of the myth of their creative process, even as their stated motivation might be personal, emotional:

Maybe that’s why I write—in a journal. That feels “right.” I know I’m alone, that I’m the only reader of what I write here—but the knowledge isn’t painful, on the contrary I feel stronger for it, stronger each time I write something down. . . . I can’t talk to myself, but I can write to myself.

(But is that because I do think it possible that someday someone I love who loves me will read my journals—+ feel even closer to me?)

Of course, I have just performed a messy conflation. There are differences in form and idea among the diary, the journal, the poet’s notes, and the field notebook, and the publication of each presents different enticements as well as moral challenges. The field note in particular remains a kind of trade secret in the social sciences and their publication is sometimes considered an embarrassment if not a scandal, as when Bronislaw Malinowski’s notebooks from nineteen months of fieldwork in Mailu and Troibrand communities appeared posthumously in 1967. “[A] revealing, egocentric, obsessional document,” one scholar wrote. “Gross, tiresome,” said another. They were the work of “a crabbed, self-preoccupied, hypochondriachal narcissist.” Yet they have also been called, with more hindsight, “a crucial document for the history of anthropology.”

For me, the most revealing parts of Malinowski’s notes, published as A Diary in the Strict Sense of the Term, are those which humanize the Polish scholar who more than any other transformed ethnography. On top of the observations which make up the stuff of his scholarship, he chastises himself for reading novels in his tent, a temptation he can’t resist; he suffers from constant feelings of apathy and sloth; he writes poems! Nothing is too mundane, self-incriminating, or off-topic. “Sunday, 1.18.14 [sic]. After doing my exercises I collected myself (rather slowly) and went to the village in a bad mood, for they are asking an exorbitant price to rent an oro’u—20 sticks of tobacco.”

A clever collection of essays from 1990 called Fieldnotes finds anthropologists training metaphysical microscopes on the atomic building blocks of their working lives. In the amusing first essay, “I Am a Fieldnote,” anthropologist Jean E. Jackson makes a study of her fellow scholars’ habits of note-taking. She finds them as reticent to discuss their unexamined holy rituals as any remote tribe might be.

My interviewees have indicated their unease by using familiar words from the anthropological lexicon such as sacred, taboo, fetish, exorcise, and ritual, and by commenting on our tendency to avoid talking about fieldnotes or only to joke about them (comments reminiscent of the literature on avoidance and joking relationships).

I saw myself in some of these respondents, particularly those who felt burdened by the sheer weight of material they felt compelled to collect:

“They can be a kind of albatross around your neck.”

“They seem like they take up a lot of room . . . they take up too much room.”

Some felt a perverse desire to lose their notes (a calamity that happens with unusual frequency among anthropologists, whether due to war, fire, flood, or shipping accident):

“[Without notes there's] more chance to schematize, to order conceptually . . . free of niggling exceptions, grayish half-truths you find in your own data.”

“So maybe the people who lost their notes are better off.”

Importantly, several respondents found this to be particularly true of audio tapes. The more automated the note-taking device, the greater the impulse to collect everything to the point of paralysis. The comparison with film vs. digital (and especially smartphone) cameras needs no elaboration. Handwritten notes are themselves the first stage in editing reality into its most relevant and interesting features. You can’t write down everything.

As for journalists, while I would love some day to see a book that is the reportorial equivalent of Fieldnotes, I’m not sure the raw matter of notes is often, or ever, published. I can see why—so much of what a journalist jots down is the mental work of other people, stolen from interviews, or else the dull products of immediate observation. Mehmet—red shirt, tall. Journalists’ working notebooks generally tell us little about how the writer’s mind will process the raw material, which is part of the appeal of reading private writings in the first place.

//

Everything I write begins in a softcover pocket notebook. Eventually, when I finish a notebook or have some free time, these notes migrate to a computer. I scan the pages with my iPhone and also transcribe them manually, so that in the end every note exists in triplicate: as a hard copy, as a scanned PDF, and as one or several word processor documents. Many things might happen to a scrap of writing then, but most often nothing at all. 90% of any notebook is chaff: grocery lists, book recommendations, purple prose written at bus stop, bad story ideas, descriptions of boring days, eavesdropped lines that don’t signify. The last 10% is where the published writing comes from. I haven’t found a more efficient system than that.

Recently, journalist Wilfred Chan asked journalists and nonfiction writers on Twitter to describe their note-taking workflow, specifically for generating story ideas. I liked reading what others had to say on the subject and briefly described my own system:

all stray thoughts go into pocket notebook, later I scan, transcribe, and sort the material among different word documents (e.g. a document for story ideas)

Chan asked how I stayed consistent in this admittedly inefficient process, which has long since become automatic for me. At first, I wasn’t even sure. On reflection, I said:

Mostly brute force, but system evolved over many years to feel balanced/good for me. Having a “dump everything here” notebook permits me to be disorganized and spontaneous—more gets written. Then, transcribing and organizing is good idiot grunt work when I am feeling burned out.

These are the systole and diastole of writing for me: spontaneous, first-thought-best-thought scrawling on the one hand, and rote transcription and categorization on the other. Neither feels like writing, per se. Both are designed to camouflage the creative process from its neurotic actor. The former is ‘just’ notes; I can jot them without feeling the awful pressure of having something to say or producing work for other people. The latter is even less demanding. In theory, it is a mechanical activity that I could outsource to others, even to a computer program if my handwriting were at all legible.

In practice, however, as I perform the auto-secretarial work of transcribing and sorting my notebooks into documents—these correspond to categories like story ideas, book recommendations and reviews, and daily journals—I am continuing to write and edit, expanding on what’s already there. This happens organically, without any conscious commitment from me to “clean up” my dumping site. Again, the advantage is that I don’t even feel like I’m writing: there’s no pressure to produce something fully formed, which is a pressure I usually find debilitating. Very little of my writing involves coming up with sentences and paragraphs out of whole cloth. Almost nothing gets written linearly.

I would now add a third section to my reply to Chan: The really crucial part of this system is not the transcribing or categorizing, which may not appeal to other, less compulsive kinds of writers, but the constant presence of the notebook. You must always have your notebook on you. It is your pacemaker. It never leaves your body. If it does, you’ll die. Having the notebook with you, thinking a thought, recognizing (rightly or wrongly) some value in it, writing it in the notebook—these must become the same breathlike action, something that on reflection seems to have taken place in a single frictionless moment. It must require no conscious effort to jot something down in the middle of a conversation, on the subway, during oral surgery—if you are worried about appearing rude, think about all of the situations in which people feel free to look at their phones for lesser purposes—such that becoming a note-taking obsessive requires only practice. You must never think “where is my notebook” much less “which notebook/notes doc/app/file should I put this in” when a thought strikes. The writing must feel like an immediate extension of the mind.

Does it go without saying that you must like your notebook? It sounds silly, but a notebook that falls apart, or that doesn’t fit in some of your clothes’ pockets, or that looks garish or trendy or cheap, or that feels cheap to the touch, or that draws attention to its materiality in any way—these failings will introduce a speed bump in the process of thinking on the page. It will create a hesitancy, a sub-perceptual reason to wait, to delay, and in this gap—“I’ll write it down later”—thoughts will be lost.

I feel naked without my notebook, a ruled pocket Volant from Moleskine, sold in packs of two, which does not fall apart under any conditions, which fits in the front or back pocket of slim jeans, which contains 80 pages many of them tearable (but not easily torn), whose covers are soft and pliant and so not painful when sat upon, yet water-resistant and tough, made of multiple pieces of heavy stock paper glued tightly together. This is not an advertisement. Find the notebook that works for you. I found mine and have stuck with them long enough. I number them and am now writing in #65. If I can’t find my notebook, I panic, but I have only truly lost a notebook twice, and each time a stranger either called the phone number or came to the address I’d written in the front of the book to return it to me. This has happened on two continents. The promise of reuniting a notebook and its owner seems to produce a spiritual commitment among people of all kinds. (“I wrote my name and address on the front page, offering a reward to the finder,” Bruce Chatwin, legendary devotee of moleskine notebooks, wrote in The Songlines. “To lose a passport was the least of one’s worries; to lose a notebook was a catastrophe.”) Yet you may lose a notebook; accept it. So many things seem filled with the intent to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

//

A story usually begins its life as a one-line idea in one of my notebooks. That idea eventually goes into a “Story Ideas” document on my desktop. I browse this document from time to time and occasionally pick up an idea, start to research it, and, maybe, eventually, write a pitch. Even that part of the process can take years. If successful, I’ll pack some notebooks into a bag and go to work. This story, for example, continued its life as three or four notebooks which I carried around with me on a trip to the Caucasus. In them, I wrote down every stray observation, transcribed every interview, and copied every relevant piece of text or map I encountered and might want to have. After I got home, over several weeks, I transcribed everything into a document labeled “Circassia Notes,” then condensed these by moving the interview transcriptions. The result was a 22-page single-spaced collection of quotes, facts, observations, structure ideas, half-sentences, and short phrases from my reporting and research. They were in no sensible order until I began to move the pieces around inside the document. There are pieces of software designed to facilitate this corkboard method of writing, but for something of magazine-article length, I find any word processor works. You just need the copy/paste function.

This is the process that works for me. It could not work without computers; it would be absurd to attempt it in longhand, just as I wouldn’t try it with a chisel and stone tablet. So I recognize that like all forms and approaches to writing, my process is the result of the interchange between technology and thought, between medium and method, each evolving the other into being. Computers, the Internet: these are now handmaidens of writing, not the enemy. If they have changed the nature of writing, well, so did the printing press and the alphabet.

And yet, despite myself, I sometimes feel a luddite concern. I worry about the attention wars—the trillion-dollar conflict over our eyeballs—which have turned the unfocused inattention and boredom which is a prerequisite for note-taking into a rare commodity. Some degree of idleness precedes all note-taking. Is it still attainable? Can we still enjoy a thought to ourselves? The concern animates Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing, an unusually captivating self-help book and polemic against productivity and distraction, twin forces which she views as nothing less that a “colonization of the self”:

A simple refusal motivates my argument: refusal to believe that the present time and place, and the people who are here with us, are somehow not enough. Platforms such as Facebook and Instagram act like dams that capitalize on our natural interest in others and an ageless need for community, hijacking and frustrating our most innate desires, and profiting from them. Solitude, observation, and simple conviviality should be recognized not only as ends in and of themselves, but inalienable rights belonging to anyone lucky enough to be alive.

I will never love my phone, or even much like it, but I am compelled to use it in ways not just wholly different from but in active conflict with my compulsion to write about the world. For this reason, it is important to me that, despite slick corporate efforts toward unifying in one convenient object all human tools of creation and consumption—and despite the fact that I keep both on me at all times—it is important that the notebook and smartphone never merge.

I try never to impart dogma, but I’m dogmatic about this. The thing you take notes on should not get emails. It should not text. It should not contain any information that did not come from your mind and the physical world around you, because that is what makes it a rare object in your cabinet of cared-for objects, a totem that sees and thinks with you rather than for you. It is a tool that relies on your perception, like a loupe or telescope, rather than an object that regurgitates your and everyone else’s life and already seems to know everything worth knowing—so why write at all? Whenever I have tried to take notes on a phone, I am always urged to do something else: to Google something, to look up a definition or translation, to send a text or take a picture. The phone can do everything except permit me to be bored, or to exist in a prolonged state of unknowing. By contrast, a notebook refuses the urge to look elsewhere at the moment of frustration. In a notebook, you must keep going. You must let the thought after this one arrive. It does not usually feel like writing is happening when it does, but that’s precisely where the writing happens, in the act of what Germans call Sitzfleisch, a kind of sticktoitiveness amounting to the ability to sit and work beyond the urge to be relieved of one’s own thoughts.

This isn’t to say I’ve never typed something furtively into the Notes app. Sometimes it’s the closest thing at hand; sometimes I don’t want to advertise the fact that I’m writing down an observation about the people around me. (To most people, phone use is evidence of inattention, and by staring at your phone you occasionally find yourself becoming invisible, even as interesting things take place around you.) But these are exceptions. The notebook is better, both for the above reasons and because with any practice you will be faster, shrewder, sharper in your note-taking, less tempted to abandon the dull process of shrinking the world into a written observation for other, faster methods—photos, audio recordings—which quickly proliferate and overwhelm, and do not produce the kind of note-formed thoughts that make writing possible.

The Volant line has become increasingly rare at stationary stores and even Moleskine outlets; often, what stock there is has been discounted. I am worried the company may be planning to discontinue it. (It’s the same nightmare Chatwin once faced in the years before the French notebook manufacturer was bought and rebirthed by an Italian entrepreneur in 1997.) If anyone is looking to buy me a birthday gift, $230 worth of lined pocket Volant notebooks can be purchased in bulk at the link here. At my current rate of use (one notebook every 2-3 months, unless I am actively reporting a story, in which case I might go through a notebook in a day and a half), such a stash would last years.

More important, they would sit in fresh shrinkwrapped ranks on my bookshelf, exuding potential and focus, forgiving me my all bad habits and inadequate powers of observation. All that is past, whisper the unused notebooks. I feel like one of Jackson’s respondents, who speaks of “a strong awareness of the physical notes, in a symbolically important place next to my desk at home . . . a mana quality.”

Recommended Reading

The greatest living novelist ever to let me live in his basement, Tony Tulathimutte is the author of Private Citizens and the founder of CRIT, a writing school in Brooklyn. Tony writes:

Walter Scott's Wendy series (currently a trilogy which includes Wendy's Revenge and Wendy, Master of Art) is probably the most accurate account of being a twenty-something art striver, a kunstlerroman that truthfully places the drinking, petty career envy, social strikeouts, pompous workshops, and regretted texts at dead center. The faces are playfully expressive in their ecstatic crudeness, from dopey smiles to permanent Edvard Munch screams to this:

For some reason it's not easy to get the first book, but it's well worth the hunt. Full disclosure, I'm seriously considering a Wendy tattoo.

xo,

Ben

What a fantastic entry. I have always meant to keep a notebook, but then again I have always meant to write consistently, and maybe there's a connection between the laziness and the dearth of productivity. I've started a few over the years, then got self-conscious about the cascade of bad ideas and useless thoughts. But I like your insights about the idleness being the point. Thanks for the glimpse into your process, even if you didn't mean it as advice. :)