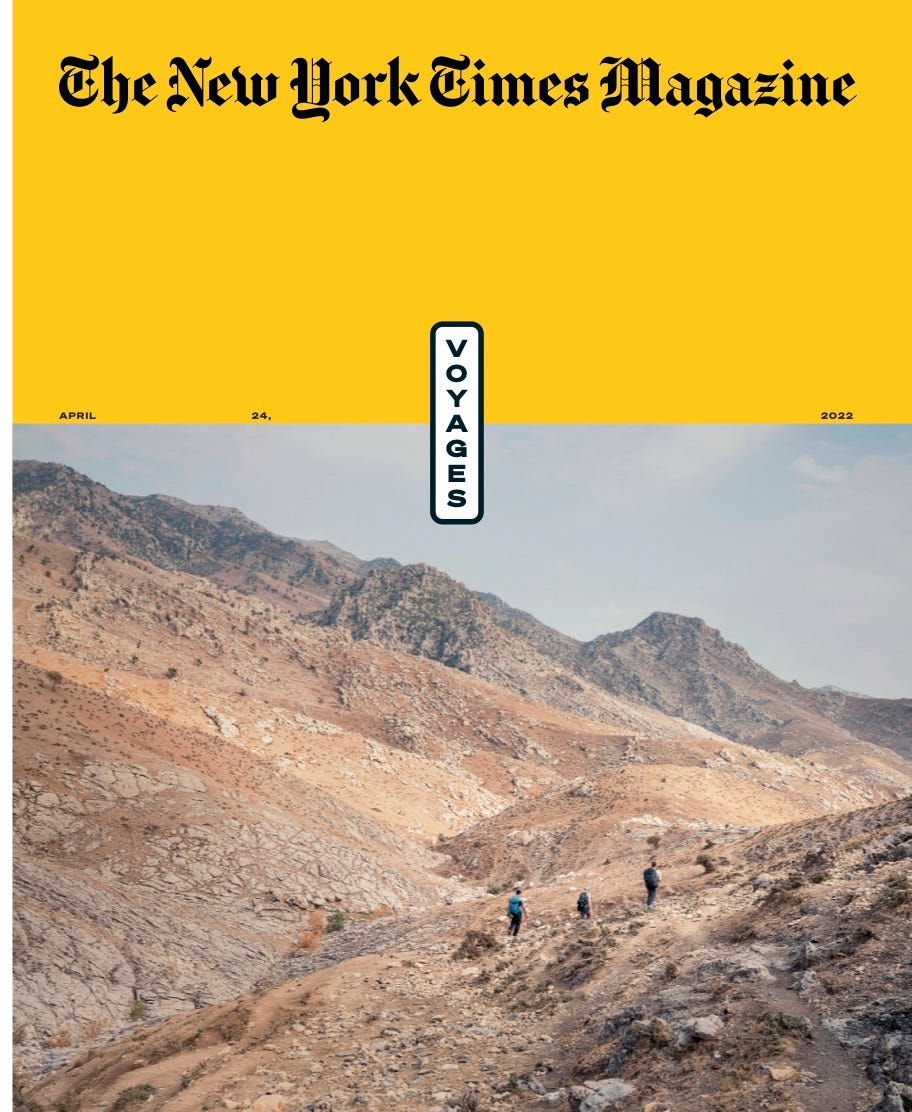

In April, The New York Times Magazine published “Mountain Time,” a chronicle of the first long-distance hiking trail in Kurdistan, on the cover of its semi-annual Voyages issue. It is a long story and the product of many drafts; a lot of worthy material did not make the final cut due to length restrictions and other factors. In this month’s newsletter, I’m sharing a self-contained outtake that served as an alternate ending in early drafts. (My editor suggested it might be too downcast a note to leave readers with.) You’ll notice some stray phrases that did make it into the final piece.

For me, revising a story always produces a lot of unused scenes, especially early on, as I discover how many settings and scenes the story will tolerate in magazine form without losing its momentum—always fewer than I think when writing the first draft.

To read the published story, click here. To listen to the audio version on Audm, click here.

//

One day, Lawin Mohammad took me by car from Erbil to visit a cluster of towns and ancient ruins 50 miles west of the current trailhead. “These are the most important sites in the region,” he told me as we drove out. “It really makes me feel proud to be born in this area. You’ll see temples, shrines, churches, relics from the Assyrian empire…” The latter included, at Khinnis, monumental bas-reliefs celebrating the canal system of King Sennacherib, who ruled Assyria, destroyed the City of Babylon, and has a walk-on in the Old Testament.

Yet none were part of the Zagros Mountain Trail, and perhaps never would be. “If the security situation were different,” Leon McCarron told me on our first day of hiking, “we could go from Alqosh into the mountains, to Amêdî in the north, and from there to Shush. Now that would be dramatic.” The addition would make the full trail more ambitious by one-third. It would also bring hikers through densely mined terrain around the ancient hilltop city of Amêdî and within a few miles of the heavily bombed borders with Syria and Turkey. “It’s pretty far from where the PKK hideouts are,” McCarron said, “but until there is zero activity, we’ll stick to where we are.”

In the car with Mohammad and me was Ninwaya Petros, a Christian Kurd and obsessive hiker who worked for a French NGO rebuilding churches destroyed by ISIS. Petros spent much of his time in Mosul and knew the area and its Christian communities well. That spring, he’d supervised the construction of a wooden chair for Pope Francis to sit on during the pontiff’s March visit to Qaraqosh. The chair is still on display in the Al Tahira Church with Petros’s name engraved on the back. When strangers message him with offers to buy it—sometimes offering obscene amounts of money—he turns them down.

The Ninevah Plains are the rumpled edge of Mesopotamia. To the east emerges the limestone spanakopita of the Zagros fold-and-thrust belt. Most villages in the area are found in the seam of a long stretch of low hills that start north of Mosul, around Duhok, not far from the Syrian border. The landscape is sparse desert. Every mile or so is marked by a single leafless, crooked tree standing in an expanse of brown dirt beneath the ridge line. We passed a stretch of hills hiding a U.S. military base from which my country sends out air strikes over Iraq and Syria. Even in relative peacetime, the region is contested; a majority of its population is not Kurdish and there is some argument whether the area is or ought to be part of the autonomous Kurdistan Region. Foreign diplomats do not visit for risk of accidentally stepping across an invisible border.

There is only one road in or out of Alqosh from the highway. Our car stopped at a checkpoint for a half-hour while the guard tried to reach his superior. “It’s the weekend,” Mohammad said. ”Everyone is sleeping in.”

”ISIS was on the road here, just beyond the checkpoint,” Petros said flatly. We were parked on the shoulder of the road in question. “They couldn’t get into the city.” Mosul was 28 miles away, and the Mosul Dam, which ISIS briefly held, and which experts fear may collapse in coming years owing to the soft gypsum deposits beneath it, shimmered in the distance. “After the fall of Mosul, a lot of people from Alqosh moved to the U.S.,” Petros said. “They go to Michigan. Have you been to Michigan? It’s all Alqosh out there.”

One proposed start for the Zagros Mountain Trail is the Rabban Hormizd Monastery, a Chaldean site carved into the mountains in the seventh century. We hiked up the stone stairs to the monastery gates. Mohammad chatted with the caretakers about paths in the area—one purpose for our day trip was trail reconnaissance—but was careful not to describe the Zagros Trail as tracing a path through Kurdistan, since Chaldean Christians in Alqosh do not often locate themselves within that conceptual territory. Mohammad wasn’t bothered by it. “Northern Iraq” was fine. He was used to trail diplomacy, and the trail was the only thing that mattered.

We followed a few monk paths opposite the monastery but they only went to some caves. Within an inner sanctum of the church, a portal led to a network of underground tunnels where, Petros said, Christians hid themselves over the centuries during times of slaughter and forced conversion. The tunnels did not lead anywhere, either. In one of the caves was an inscription in Aramaic, which Petros translated. “Leaving home is harder than starving,” he said.

Even if there were no security concerns, Mohammad and McCarron have not yet found a suitable trail from Alqosh to Lalish, a temple complex that is the holiest place in the Yazidi faith. Each time they walked it, they found themselves pushed toward the highway or lost in featureless hills, the kind of awkward liminal spaces they wanted to avoid. (“Well-designed trails minimize linking sections,” McCarron told me.) We drove along the highway for an hour, turning onto a side road where a controlled flare sent up an eternal flame above an oil well. The Yazidis are a minority religion among the Kurds. Their faith permits neither conversion nor intermarriage, and they are therefore small, with fewer than a million members in Iraq: a minority with a minority. Their history counts 72 massacres, sometimes described as genocides. The 73rd came at the hands of ISIS, who like other persecutors in their past viewed Yazidis as infidels and devil worshippers exempt from codes of wartime conduct. Yazidis are overrepresented among the 1.2 million internally displaced people in Iraq, most of whom are victims from the war on ISIS. More than two-thirds of the internally displaced currently living in refugee camps arrived in 2014. Others fled to Syria and have yet to return.

The entire complex of Lalish—an agora of monumental white stone—is sacred. We left our shoes in the car and entered barefoot. The stones were warm and soft. They are oiled every day. We stepped carefully over the lintels in doorways, which are holy, exploring a Mediterranean assemblage of layered platforms, ivy-covered alcoves, bridges, colonnades, buttresses and towers, shaded by eight-sided sun shrines and eucalyptus trees. Hundreds of Yazidi families had come to picnic—it was Friday, the start of the weekend in Iraq—sitting together on blankets in nooks and on balconies. Children ran through the alleys playing with rubber snakes.

The spiritual guardian of Lalish, Baba Chawish, was sitting in his study smoking hand-rolled cigarettes through a long ebony holder. The room was filled with images of peacocks. On a table were bags of sunflower seeds and cartons of baklava. For two decades, he has overseen the sanctuary where Sheikh Adi, who founded the first Yazidi community and who is believed to be an avatar of the Peacock Angel, lies entombed. Lalish is the holiest spot in the world, Baba Chawish explained. All Yazidis are enjoined to visit at least once in their lives. Humanity began here. A little over a century ago, the complex was occupied by the Ottomans and turned into a madrassa, and the Yazidi symbols were destroyed. But they have rebuilt; they survived. I asked how old the complex was, which turned out to rely on a common misperception. Lalish could not be dated, he said. It was the oldest place in the world.

Baba Chawish welcomed the idea of a hiking trail, he said. All are welcome in Lalish. But he was more preoccupied with the thousands of Yazidis still displaced in camps and, in the cases of women, living as slaves in ISIS cells in Syria and Iraq. Previously such women would have been cast out of the Yazidi community; Baba Chawish has told reporters they will now be reconsecrated into the fold. “There are thousands of our people who are still in the hands of ISIS and no one has tried to get them back or to help us. Why does nobody help us?” He had read that, in the United States, millions of dollars are spent to save endangered animals from extinction—well here was an endangered religion! An endangered people! Sinjar was free now and liberated, yet still the Yazidis were displaced. They didn’t need food and water, they didn’t need work, they didn’t even need homes. They needed a guarantee that neither ISIS nor any other group would rise up once more to kill and enslave them. He sighed and took a long drag on his cigarette. Tendrils of smoke unfurled, filling the room. “Until when will we live in the tents?”

In the evening, a youth group swept Lalish alley by alley and stone by stone with short-handled brooms. Mendicants paced through the inner courtyard of the shrine to Sheikh Adi, kissing trees, stones, alcoves and doorways in a patient ritual circuit. A lilac gloom fell across the world. We drove home. I said to Mohammad that Lalish was maybe the most beautiful place I had ever seen. I wouldn’t want visitors like me to overrun and spoil it. Mohammad disagreed. Such things could not be spoiled. “It’s a shame the trail can’t reach here right now. Whenever we can, we drive people out to see it. We’ve scouted a trail, but only two or three times. There are problems. Mines, drones, PKK. I know it will be solved. Sooner or later, it will be solved.”

//

I know I’ve been quiet—publishing this long story dominated these past months—but I’m looking forward to sharing outtakes, thoughts, and process notes, plus whatever else strikes me as interesting about my work and life, in this space, approximately monthly. I am also teaching my occasional weekend course on freelance writing online for the first time this June, where I am planning to use this story as a model, so I may come up with other things to say about it over the summer.

xo

Ben

P.S. Here’s the print spread, featuring Lawin Mohammad, Sadiq Zebari, me, and Emily Garthwaite, in a photograph by Andrea Frazzetta.