[Read Part 1 here.]

At the sound archive office in Mitte, Sarah lamented that most of the shellac records had yet to be studied. They sat unheard in silent storage. In all likelihood, at least some of them will stay that way. Thus does immortality live adjacent to oblivion. Records are not the same as memory and data is not information. With few exceptions, what we know of these soldiers’ lives, apart from the few biographical facts Doegen jotted into his log book, is exactly nothing.

//

Stories of escape find each other in strange ways. They congregate with a frequency greater than chance would suggest in Berlin, which sometimes seems to lie at the center of every exodus or errand that ever crossed the European plain.

In 2005, a historian working at the National Archives in Delhi came across a sealed envelope labeled, in pre-independence fashion, “His Majesty’s Office.” The envelope contained the trench diary of Jemandar Mir Mast, whose brother, Mir Dast, is well-known as a World War I-era hero of the British Raj. Mir Mast’s story—one of defection, imprisonment, and exile—remains relatively obscure, although it is among the more fantastic that Berlin’s Half-Moon Camp, and the Great War, have to offer.

In The World’s War, writer and presenter David Olusoga narrates the story of this Muslim POW with “the face of a born survivor,” born in a mountain village on the India-Afghanistan border. Like his brother, Mir Mast was an Urdu-speaking Afridi soldier thrust into a European war. The state of affairs on the Western Front is indicated by the English-Urdu vocabulary list he maintained in the trench journal, which includes words like “blanket,” “hungry,” and “please” alongside other, more mysterious entries: “testicles,” “breasts,” “honeymoon.” Who knows what use he made of such translations? What is known is that, in 1915, on the night of March 2, Mir Mast led a group of 23 other Afridi sepoys across no man’s land into German territory, where they defected just before the Battle of Neuve Chapelle. No command or commitment to “jihad” was required; death seemed certain to many of the soldiers who had survived the nightmare of winter, and who now faced German gas, not all of them for the first time. After watching comrades fall at Ypres and Givenchy, Mir Mast’s band of defectors would have viewed the preparations for Neuve Chapelle as suicidal. They believed only the Germans could save them. During his interrogation, Mast told a German missionary and Urdu speaker that all the Germans needed to incite further defections was to say, “‘We’ll give you a Mauser pistol and a good German rifle.’ That’s enough, all of them will come.”

Mast was a tall, trim man with jug ears, sloping shoulders, and hard, determined face. After his defection, he proved himself invaluable to the Germans, providing them with maps and military positions of the Khyber Pass, the imperial passageway that lay near his family home in the Tirah Valley. The Khyber Pass was crucial because it was through this artery that the Emir of Afghanistan would—if he could be convinced by hopeful German emissaries— launch an invasion of British India. It was theorized that an uprising would split British attention between the war and their own imperial concerns. Inciting such an uprising was the orientalist Oppenheim’s plan; he believed it would be an easy thing to convince Emir Habibullah Khan to declare war against Great Britain and thread his army through the Khybar. Toward this end, delegations were sent to Kabul as early as August 1914, even before the war had begun.

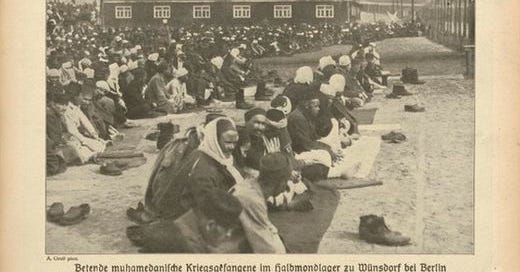

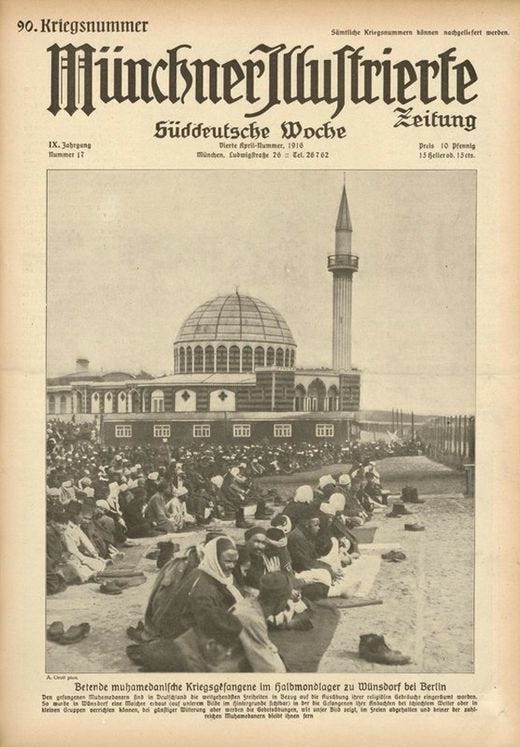

After his defection, Mir Mast was sent to the Half-Moon Camp, where he became, as far as his captors were concerned, a convinced Jihadist. There his story temporarily goes quiet. But a few years later, a German expedition set off to Kabul with direct orders from Berlin to incite an Indian revolution. The team was led by Oskar von Niedermayer, an orientalist, artillery officer, and spy (often considered the “German T.E. Lawrence”). Niedermayer was enlisted by Oppenheim and the foreign service. Included in his expedition were a German diplomat, a Turkish liaison officer, the Indian nationalist and Marxist intellectual Mahendra Pratap, the Islamist Abdul Hafiz Mohamad Barakatullah, and Mir Mast himself, sprung from prison.

The expedition of fifteen men traveled across Europe on the Orient Express disguised as a traveling circus. The subterfuge was imperfect. Their luggage, traveling separately, was stopped in Romania, where customs officials discovered that bags labeled “tent poles” contained field radio aerials; a subsequent investigation uncovered machine guns and military supplies. The band waited in Istanbul at the Pera Palace Hotel until more shipments, better disguised, arrived in early December. From Istanbul, they crossed the Bosphorus and boarded a train to Baghdad.

The expedition was in possession of a hundred thousand pounds worth of gold bullion as well as letters from Kaiser Wilhelm II and Sultan Mehmed V. They crossed the Great Salt Desert in the heat of summer, followed Alexander’s route across Persia, and, traveling at night and avoiding the patrolling Cossack and British units, reached Afghanistan. In Kabul, anti-British sentiments ran high, and the party arrived in August 1915 to celebratory fanfare. Two months later, they were able to meet with the Emir, where terms were discussed.

In the end, Germany was unable to supply the military support Afghanistan required—or claimed to require, the very request being somewhat obviously impossible to all parties. The Emir outwitted Oppenheim, playing both sides of the conflict while awaiting news from London. Niedermayer returned to Germany in 1918 and went on to pummel Communists in 1920s Munich.

The other members scattered to their respective homes or lands of desire. According to a secret report on suspected Indian deserters found in the British Library, Mir Mast made his way from Kabul to Tirah. In June 1916, the British India Corps sepoy and German war hero, espionage agent, deserter, and prisoner arrived at his family home in the Maidan Valley, which today lies in a contested region along the border of Afghanistan and Pakistan. It is also reported, although not verified, that it was a descendant of Mir Mast and Dir Mast, Dr. Shakil Afridi, who helped the CIA create a fake vaccination program in Abbotabad in order to gather the information that led to the assassination of Osama bin Laden.

//

The secret phonograph commission, which eventually collected over 1,000 wax cylinders and 1,600 shellac discs from the Half-Moon and other POW camps, was declassified in 1919 and forgotten for a long time. Wilhelm Doegen kept working toward his museum, but after Hitler came to power he was dismissed from his position due to rumors about a Jewish grandparent. After the war, he resumed his teaching duties in Berlin, where he lived the rest of his life. The archives were scattered. After 1945, the Berlin Phonogram Archive was relocated to the Soviet Union. By accident, all the documentation was left behind. The recordings were returned to East Berlin in 1960, locked away in a vault, and brought to the Museum of Ethnology, where the documents had remained, only in 1991, after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Of 2,600 recordings of prisoners speaking and singing in 250 languages, most remain untranslated and unanalyzed. The speakers came not just from India and Madagascar but from the Caucuses, Tunesia, Algeria, Siberia, the Tatars, Korea, Nepal, Malaysia, Persia, the Basque country, and Portugal. In other camps, Doegen required Christian prisoners from Ireland, France, and England to recite Luke’s parable of the prodigal son into the gramophone. The archives are therefore home to several dozen recordings of this parable, the same story uttered in every English accent. Some of the wax cylinders are broken or covered in mold. The copper galvanos are in good condition, though, and the museum has made new copies. In 2014, the year I learned of the archive, the wax cylinders came under the purview of the German Research Foundation in anticipation of the centenary of the war. Because the recordings were produced without consent, they are not accessible online.

Germany’s “jihad” strategy failed among the colonial prisoners. It’s not hard to imagine why. In one recording, a prisoner named Chote Singh recites his scripted line (“The German kaiser looks after me very well”) then laughs. Other subjects practiced clever forms of resistance, including lying about their hometowns, perhaps in order to throw off the Germans’ anthropological data. Photographers report that prisoners would often purposely play dumb to thwart efforts to pose them in “scientific” positions. Nevertheless, camp commander Otto Stiehl thought his photographs would make for good anthropological studies on racial distinction. A few years later, the Nazis agreed, and the various projects of the Half-Moon Camp were reworked toward the ideological ends of Rassenkunde.

Today, Wünsdorf is a small, oddly shaped town surrounded by the overgrown relics of a century of military attention: former barracks, weapons laboratories, bomb shelters, and conspicuously empty fields of gravel and young weeds. During World War II, Wünsdorf was home to the Nazi command centers for two competing intelligence organizations whose buildings were disguised as rural townships with clay tile roofs and waddle-and-daub construction. The disastrous Barbarossa campaign was born there. Afterward, the largest Soviet military base outside Moscow lived in (and, most elaborately, beneath) Wünsdorf, complete with daily train service to the Russian capital. Almost nothing at all remains of the Half-Moon Camp, not even the mosque. One must search for the small British-built cemetery where the 206 prisoners who died at the camp are buried. History and nature have together done their work.

//

It’s my 30th newsletter. Thanks for reading. Excepting one or two long hiatuses, I’ve managed to post approximately monthly in this space for four years.

If you’re new to the newsletter or to me, you can check out my most recent published writing, a chronicle of a month hiking across Iraqi Kurdistan for The New York Times Magazine. (Now also in Italian.)

Or you can read last year’s multimedia investigation into mass internment in Xinjiang, China, which I helped develop and wrote for The New Yorker, including a V.R. documentary currently nominated for an Emmy.

You can subscribe to my newsletter by clicking this button.

Eventually, I’ll use this space to talk about the book I’m writing and publish excerpts and outtakes. For now, I sometimes write posts like this one, essays involving research old and new, featuring some of the same themes and ideas I’m working on in my book. I’ve also started a more casual notes/reviews section, Little Atomies, which I (mostly) don’t email out to the normal subscriber list. (If I can figure out how to make it opt-in, I will, but so far no luck.) Recently, I wrote about some movies.

Feel free to reach out in the comments or by email with questions or thoughts. The questions readers send me have generated a handful of entries in the past. And feel free to share the post if you feel so inclined. Thanks again for reading.

xo

Ben