I have resurrected this long-dormant newsletter and will hopefully start writing here again more often, approximately monthly.

I admit that I wouldn’t necessarily trust such a statement coming from an inveterate start-and-stop-again diarist. I wrote just three posts in 2023 (short ones) and zero in 2024 until now. Well, good — I wasn’t wasting your time or mine. I envisioned this as a space to test out ideas for writing classes, to formulate thoughts I could later formalize elsewhere, to discuss my own work, to stick odds and ends from a freelance life. And I published and taught very little in the past year or two, so there was little to post about except reactions to very bad news, and I promised myself I wouldn’t make a habit of writing reactively in this way, since good writing rarely comes out of it.

I was also pretty busy this past year: walking, reading, dancing, and writing things that have not yet appeared in the world — and so I have not lacked for a venue to test out ideas. Mostly I’ve been drafting my book-in-progress, The Fugitive World, a project described many years ago here. Somehow I came to a draft of about 330,000 (bad, terrible, no-good) words in 2023 and have spent most of this year cutting that down to something approximating my book’s contracted length.

The book has been the albatross of my late thirties and I will be literally ecstatic — visions, fainting, ego death — when I finish. A couple years ago I came across a quote from David Lynch about making his first film (a notoriously protracted, zero-budget process) and felt every word of it in the center of my heart:

When I was making Eraserhead, which took five years to complete, I thought I was dead. I thought the world would be so different before it was over. I told myself, ‘Here I am, locked in this thing. I can’t finish it. The world is leaving me behind.’ I had stopped listening to music, and I never watched TV anyway. I didn’t want to hear stories about what was going on, because hearing those things felt like dying.

I also have a long reported magazine story that has been sitting in the hopper for some months (I started working on it a mere two years ago), which I’m desperate to see out in the world. And I’ve been tinkering with a few possible post-book projects. To paraphrase James Baldwin, who was talking I think about an artists’ residency, this has been a year of crouching in order to pounce.

I have also, to my surprise, been preparing to start a job, which I sort of thought I would never do again. This month I’ve joined the English department at Case Western Reserve University, where I’ll be teaching classes in writing, literature, and, especially, journalism (it’s an endowed position intended for a working journalist). My partner and I are moving this month and will thereafter “divide our time” between Ohio and Berlin. It’s a cool department and a frankly unbelievable job, which is how I was tempted away, for at least some of the time, from the greatest and most livable city in the world. And I have loved teaching both while a grad student at Iowa in various forms since then, particularly at the Berlin Writers’ Workshop, where I recently stepped down as director. So despite my almost hallucinogenic trepidation about living in the United States after a decade abroad — moving to the U.S.? Now? In 2024?? — I’m looking forward to a change.

*

I was advised by a colleague that my first class should ideally work to “establish my brand” in the department and among students. I decided to put together a class called “Free Press and Protest” about social movements and the way they are documented, discussed, and remembered. I was obviously thinking about the Gaza ceasefire encampments from this spring. But I was also, more generally, thinking about the themes of my book and my reporting, and the sort of things I’ve come to care about — my themes, as they say.

Generally, I don’t overlecture in the classes I’ve taught. I like guiding discussions but I’m not an expert in any field, certainly not journalism, and don’t find lecturing pleasurable anyway. But it is surprisingly difficult to maintain a Socratic method for 80 minutes straight. One does tend to opine, and so, just in case, I’ve been investigating my thoughts about the “free press” of my course’s title, and what, if anything, it might have to do with protest.

The first thing that has came to mind is that both are fundamentally disobedient activities. This does not mean journalism is itself an act of civil disobedience. In fact, most journalism is not visibly disobedient in any way. Much of it is of the “service” variety: a new business has opened in town, a highway is undergoing repairs, a college team has won the homecoming game. It is a profession prone to self-mythologizing but, broadly speaking, most journalism is tranquil.

In those countries with robust traditions of a fourth estate, and among those who interview politicians or chase corruption, journalists (ideally) tend to strive for fairness and accountability while maintaining adversarial (or else, simply, neutral) relationships to power, but even this does not usually rise to the level of civil disobedience.

As the Israeli journalist Amira Hass puts it, “A journalist's job is to monitor centers of power.” Monitor is a good word for it. Working journalists I know are cautious of appearing one-sided and allergic to the charge of activism, even as some work alongside activists — and are guided by or parasitic toward activists — in their quest to reveal injustice or “afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.” These are tensions inherent to the form, and they are not shared by all who call themselves journalists. But they are common tensions under the banner of monitoring centers of power and have produced standards of behavior that, for a short period in the middle of the twentieth century — the Walter Cronkite years — generated an impressive amount of public trust and accountability.

Underlying these accomplishments is the fact that journalists publish information they aren’t supposed to have and that powerful figures may not want the public to know. Even if most journalism is not civil disobedience, the social conditions that tolerate civil disobedience are the same as those that tolerate a free press. Both are subcategories of free expression, which can only be assessed as free when someone, somewhere does not want something expressed.

Such conditions, attenuated as they may be by place and time, require a baseline degree of tolerance within those centers of power for dissent and an understanding that the friction caused by disobedience is somehow alchemically necessary for a society to function, even if they create — in the view of the powerful — problems and inefficiencies. Even if they make people “feel unsafe,” even if they result in injury or ruin.

Such tolerance may stem from the fear of losing power or legitimacy in the eyes of subjects or peers, but it is indeed tolerance. The state, a rather significant center of power indeed, has the final means of physical coercion; the rest of us do not. In the U.S., there is this fundamental similarity between activists and journalists: they can only throw their bodies behind their principles and persist in the belief that First Amendment conditions will hold. For an example of what happens when authorities believe they no longer need to be tolerant of such disobedience, we can look to Israel, whether the killing of Shireen Abu Akleh or the military targeting of media workers in Gaza, where nearly 100 journalists, almost all of them Palestinian, have been killed since October 7.

My position, which might be conservative, is that traditional journalists (a weak phrase I will not unpack) should not be committed activists — there are good reasons to keep these roles separate — but journalists do themselves no favors by pretending their work is categorically different from other disobedient forms of expression, that they do not, by virtue of their work, throw their lot in with all those whose expressions intend to disrespect power. It seems pointless to persist in the myth that both “sides” are equal or that we can divest ourselves of a natural affinity for disobedience, since our own work depends on the same refusal to obey that animates protest — an activity, I should add, that encompasses right-wing insurrection as well as progressive picketing.

To say journalists live in this pincer is to say that skepticism is the journalist’s resting state but the powerful deserve the larger share of it. When journalists are overly credulous of official accounts, when their skepticism toward perpetrators of civil disobedience outweighs their skepticism toward the politicians, police officers, spokespeople, and stakeholders condemning it, something is fundamentally wrong with their reportorial antennae. The signal is not clear. Likewise, when journalists find themselves nodding along to abstractions that short-circuit the drive for evidence: claims that a contemporary protest against a hugely asymmetrical war is driven by “ancient hatred” (in President Biden’s language) or that another such protest amounts to “despicable acts by unpatriotic protestors and dangerous hate-fueled rhetoric” (in Vice President Harris’s), something has gone wrong.

So the violent clearing of encampments across the U.S. this spring by militarized riot police, and the brutalization of young, mostly non-violent protesters (using tear gas, rubber bullets, billy clubs) was on my mind when I was asked to design a fall class. The current plan is that we’ll read a few whole books — probably Vincent Bevins’s If We Burn, Sarah Schulman’s Let the Record Show, and Omar Robert Hamilton’s The City Always Wins — together with excerpts, articles, reviews, and other things, including some films. I hope to keep the class responsive, and expect we’ll want to improvise around the flood of chaos known as current events. I am very open to recommendations so please drop me a line if you have any suggestions, historical or contemporary.

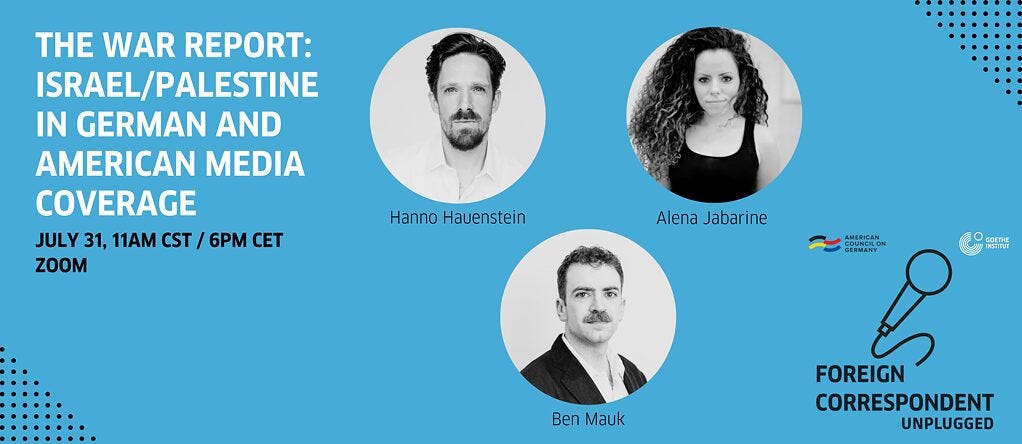

Relatedly, on July 31, I’ll be speaking as part of an online panel on “Israel/Palestine in German and American Media Coverage” on July 31 for the Goethe Institute in Chicago with fellow journalists Hanno Hauenstein and Alena Jabarine. It’s part of a transatlantic talk series and you can register here.

xo

Ben

All the best for your big move! Beware the reverse culture shock 😄

Good luck Ben!