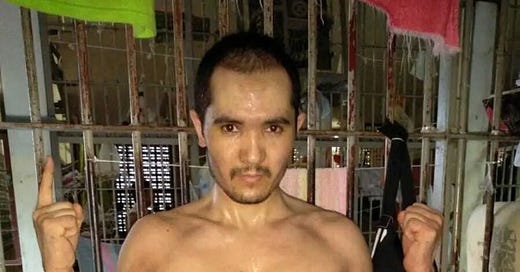

In 2017, this man — an undocumented Uyghur refugee named Hasan Imam — planned and executed a daring escape from a Thai immigration detention center, digging through the wall of his compound with a rusty nail.

Twenty men slipped through the hole before the guards noticed. Detained for years and charged with no crime other than entering Thailand illegally, they scattered into the forest at the Thai-Malaysia border.

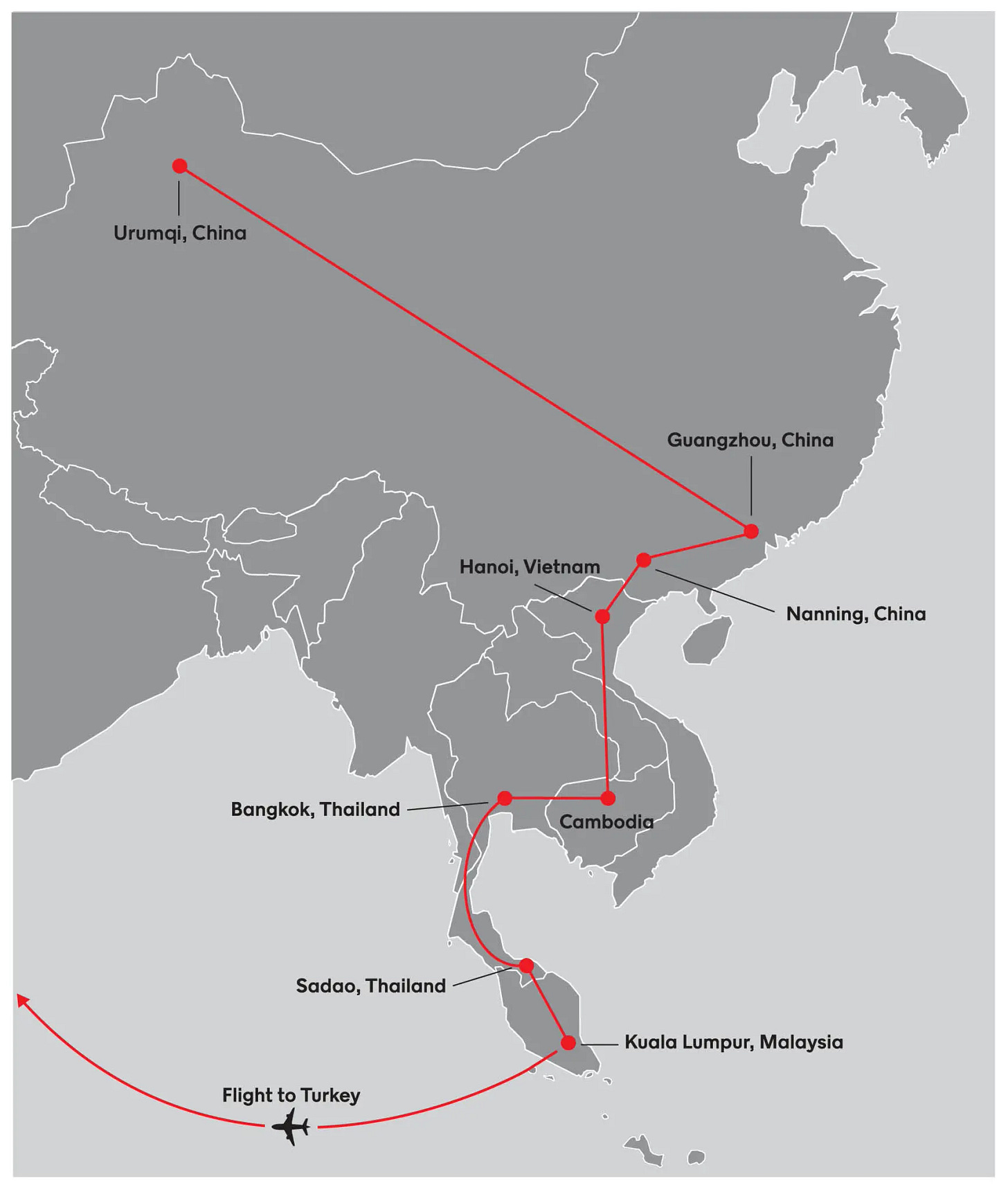

All of the men were Uyghur, part of a mass exodus of tens of thousands who fled China, many around a decade ago. Most of them were trying to reach Turkey, a Muslim country with a large Uyghur diaspora, and were traveling with their families, some of whom had already arrived in Istanbul years earlier. Along the route, they had become separated—in some cases, never to be reunited again. It is an exodus that has received little attention from the world.

Chinese authorities have branded all such migration as terrorism and demanded that other countries arrest and repatriate Uyghur asylum seekers wherever they live. These demands have become increasingly difficult to refuse. In their decade-long search for a safe haven outside China, Uyghur asylum seekers have been met with cruelty and indifference. Far from protecting them from refoulement, host countries have, in hundreds of cases from Southeast Asia to Northern Europe, bent to China’s demands to repatriate them. There is no population in the world subject to such aggressive tactics of surveillance and pursuit on a global scale.

//

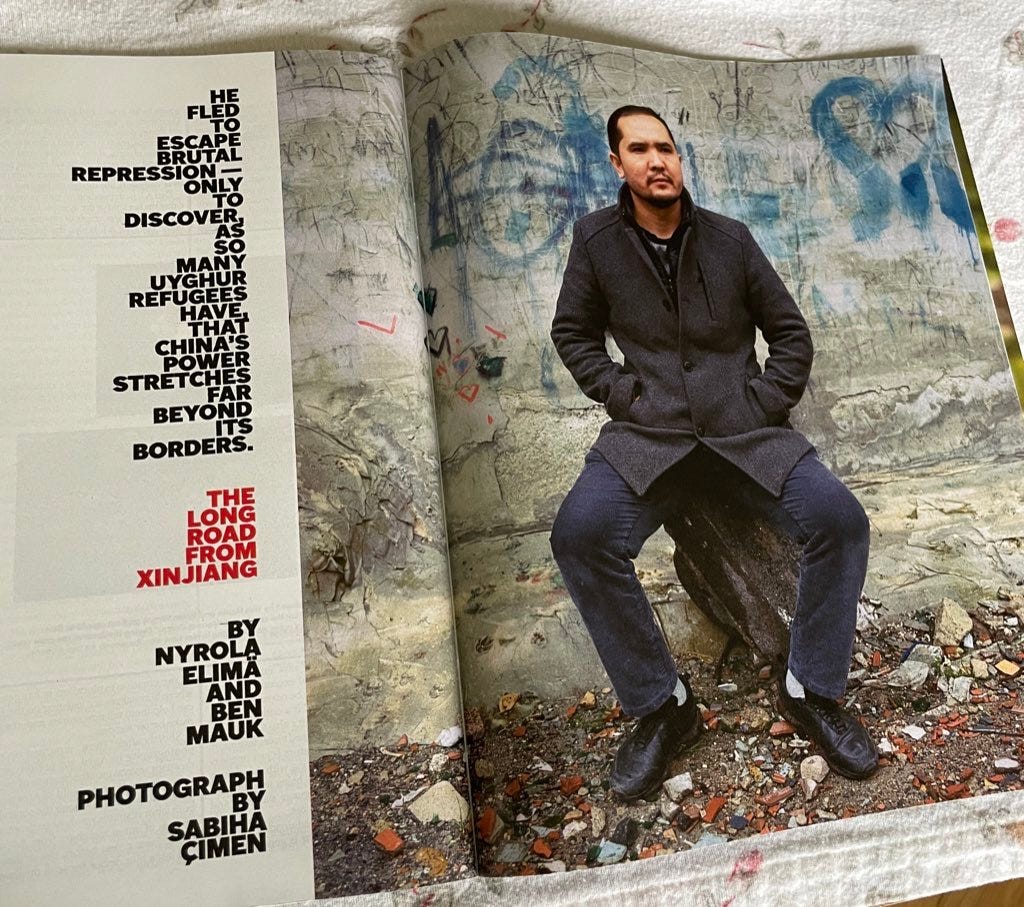

This November, Nyrola Elimä and I published a major investigative story in The New York Times Magazine. “The Long Road from Xinjiang” follows Hasan Imam’s harrowing journey out of China and across Asia in search of safe harbor. An unregistered religious scholar from a rural village, Imam crosses several borders with the help of human smugglers, becomes lost in the rainforests of Southeast Asia, and spends several years in a Thai immigration jail, eventually orchestrating a jailbreak by digging a hole through the wall of his detention center. (One of our editors at the Times jokingly described him as “Shawshanking” his way into Malaysia.) From there, he is arrested again and threatened with extradition for nearly a year. He survives police raids, disease, malnutrition, and jungle wilderness, eventually—miraculously—reaching Turkey, where he now lives. His story is frankly incredible; we spent months verifying every detail.

(Thai CCTV footage showing Imam and other detainees escaping through the walls of their detention center.)

Along the way, our story describes a decade of flight for thousands of Uyghur asylum seekers, highlighting some of the most egregious cases of indefinite detention in the world and showing in unprecedented detail the lengths to which China will go to pursue Uyghur exiles. Nyrola and I worked together for more than two years investigating the mass exodus that began around 2011 and reached its peak in early 2014, the very moment Imam fled Xinjiang. Scholarly estimates of the size of the mass exodus from Xinjiang in those years range between 10,000 and 20,000, an exodus whose scope is supported by a Chinese database we obtained. [1] The exodus ended only with the hardening of borders and the rise of the mass internment drive in which it is estimated that more than a million Turkic and Muslim people were detained in extrajudicial detention facilities across Xinjiang.

Imam was lucky to reach Turkey. Dozens who fled in those years are still detained in prisons and detention centers across Asia due to pressure from China, a major source of economic and military investment in countries where Uyghurs tend to wash up. Today, a group of nearly 50 Uyghur asylum seekers is still trapped in Thailand in a Guantanamo Bay-like facility. Conditions are dangerous and overcrowded. Our story reveals that, more than 10 years after the Uyghurs’ capture, Thailand remains under substantial pressure from China concerning all aspects of their treatment. Meanwhile, five people have died in detention, including two children. The survivors believe the world has forgotten them.

Uyghurs have even been abandoned by international organizations like U.N.H.C.R., the UN refugee agency, which like host countries have buckled under Chinese pressure.

I hope you will take the time to read this story, or listen to the audio version read by Catherine Ho, available here. It’s an exciting yarn, particularly the stories of attempted and successful jailbreaks (which turn out to be astonishingly common in Thailand; we found evidence of more than a dozen attempts involving Uyghur detainees).

But our story attempts to show not only the drama of escape or the depths of Chinese transnational repression, but also what life inside and outside of China is like for Uyghurs, including in the era before the rise of the internment campaign that put Xinjiang on the map for most Western readers. Collaborating with Nyrola, a Chinese-born Uyghur researcher and writer, made possible a story whose depth and rigor I could never have achieved alone, and I’m very proud to share her first byline at the Times. Among the best reader responses we’ve received came from the mother of a friend, who said: “I’ve read a lot about the Uyghur people but never felt like I understood the plight of them so well before. [The article] makes so clear the depth of their persecution … [they] tell the story fully in a way that often these kinds of articles don’t.”

//

Why Our Reporting Matters

I’ve reported for many years on minority issues in northwest China, from an oral history of China’s mass internment campaign to an Emmy and Peabody award-winning V.R. documentary film and New Yorker magazine story. But “The Long Road from Xinjiang” represents the most significant reporting I’ve done on Xinjiang, and the most important investigation on any subject I’ve been lucky enough to be a part of, for several reasons.

(1) Hasan Imam is a once-in-a-career subject. He has lived one of those lives whose every detail seems shaped by history, who can justifiably stand in for thousands of stories of Muslim Uyghurs who fled Xinjiang out of fear of incarceration or worse. He is friendly, sharp, and honest, allergic to embellishment, and his memory was formidable. Despite having no formal education in the Chinese school system, he studied at a madrassa in southern Xinjiang and memorized the Quran, becoming a hafiz. He lived in Ürümchi just before the 2009 riots and in Hotan during a rise in both state violence and violent separatism, and he fled at the height of the exodus alongside thousands of people.

Imam is also well-positioned to go public with his story, for reasons that are, for Uyghurs from China, incredibly rare. Because he was hidden by his family and never registered by the Chinese government, there are no records of his life and nothing to connect him with his parents and relatives in Xinjiang. (In our story, it becomes clear that, during his years of detention, Chinese officials have no idea who he is.) He might be the only person to flee Xinjiang—certainly he is one of at most a very small handful—who can speak openly about his childhood, his flight, and his ultimate freedom without fear that China will punish his family members back home for doing so.

(2) We have gathered an unprecedented amount of corroborating evidence, including dozens of eyewitness accounts from months of reporting in Turkey and Thailand.

Much of the early original reporting for this story comes from Nyrola, who for years has been traveling to Turkey and collecting eyewitness testimonies from the human smuggling route through Southeast Asia. A researcher from Xinjiang who speaks and writes Uyghur, Chinese, and English, Nyrola is likewise highly unusual, if not unique in her ability to access populations of Uyghurs and gain their trust; it is entirely because of her that this material exists, that she was able to find Imam alongside dozens of others who could corroborate various aspects of the smuggling route, imprisonment, deportation, and escape.

Through these efforts, and by finding other survivors of Thai IDCs and human trafficking, we managed to reconstruct a smuggling route about which very little was known. We spent a month reporting in Thailand, and even spoke with members of the disbanded smuggling rings, together with current immigration detainees, lawyers in Thailand and Malaysia, and former and current prison inmates, in order to reconstruct and corroborate Imam’s story—amid the larger story of a decade of exile for thousands of Uyghurs.

(3) Nyrola also was responsible for our ability to access and communicate with nearly 50 men who are still detained in Suan Plu Immigration Detention Center in Bangkok, a Guantanamo Bay-like dungeon where innocent men, women, and children are left to rot, sometimes for years and, in the case of most of the Uyghurs, for more than a decade. Our access to these current detainees is virtually unprecedented; we’ve been able to interview them directly and report on deteriorating conditions inside the facility, even publishing their messages to the world as they attempt to resist disease and despair.

(4) In the course of our reporting, we also obtained hundreds of pages of leaked government documents from China and Thailand, which, among other revelations, show how the countries conspired to violate international law by repatriating more than 100 Uyghurs from Thailand in 2015, as described in the excerpt below.

Other leaked documents we obtained from security bureaus in China demonstrate the scale of the mass exodus for the first time. (These include a database created sometime before 2018, titled “High-Risk Individuals from Xinjiang Suspected of Crossing the Border Illegally” which contains nearly 18,000 Uyghur names.) Still others include internal speeches by high-ranking Chinese officials (including Meng Jianzhu, the former Minister of Public Security) describing Uyghurs migrants as potential jihadists while acknowledging that most of those extradited in 2015 have no criminal record and are not guilty of any crime. We even obtained an internal fax from the Ministry of Public Security in 2016, sent to all Xinjiang public security units and copied to then-president of Interpol and Vice-Minister of Public Security, Meng Hongwei (who is currently serving a long prison sentence in China for bribery), stating that Chinese Uyghurs as well as foreign Uyghurs traveling abroad should be subject to increased scrutiny and thorough investigation of their overseas activities and whereabouts. We also found documents confirming that Chinese security agents use family members to track the whereabouts of and extract information from Uyghurs living abroad.

Finally, we obtained an internal letter from a Thai government-run human rights agency that reveals — for the first time — the existence of third-party countries willing to resettle those Uyghurs who have languished in immigration detention for more than 10 years. These documents, paired with the interviews and on-site reporting that make up our investigation, show the extent to which Uyghurs have been abandoned by the world.

//

Our story appeared a few days after the U.S. presidential election, amid a global polycrisis that includes the ongoing destruction of Gaza. We didn’t expect it would light the internet on fire. It is 9,000-words long, geopolitically complicated, and concerns minority Muslim peoples as well as regions—northwest China, southeast Asia—that rarely command media attention in the English-speaking world. We’ve been happy the story has done as well as it has, and that it has been shared among human-rights activists and China scholars. Its publication has led to meaningful calls for action; as a result of our work, the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China (IPAC) published a letter from 50 lawmakers petitioning for the release of the 48 Uyghurs still detained in Thailand. “The Long Road from Xinjiang” has also been praised by long-form journalism aggregators like The Sunday Long Read and made the Financial Times’ Best of 2024 reading list.

I’m confident that our story, among the most significant pieces of reporting yet published on the Uyghur mass exodus and their decade in exile, will continue to find its readers. I have more to say for another time about the difficulties involved in reporting and writing stories like this: advocating for the length and resources they deserve, working against time and indifference to get the details right. In the years it took to bring this story to publication, I have often felt pessimistic about the survival of long, ambitious pieces of narrative journalism. But I am proud to have co-written it, happy to have devoted years to its publication, and grateful to Nyrola, to our editors and fact-checkers, and above all to Imam and the many others who entrusted their stories to us. I hope you will give it some of your time.

//

[1] This sentence has been corrected from an earlier version. A non-exhaustive list of sources for the size of this Uyghur migration include Sean Roberts, The War on the Uyghurs, interviews with Sean Roberts and Rune Steenberg, and The Uyghur Community: Diaspora, Identity and Geopolitics edited by Güljanay Kurmangaliyeva Ercilasun and Konuralp Ercilasun.