This month, assuming you’re not completely sick of the subject, I’ll be writing in extravagant depth about making a virtual-reality documentary.

For my new subscribers, Reeducated is a 20-minute film about three men who survived a modern-day concentration camp for ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, China. It’s based on my reporting. I co-developed the project and co-wrote it with Sam Wolson, who directed the film. We worked with the artist Matt Huynh and animator/technical director Nick Rubin, and all four of us co-produced it with The New Yorker. Jon Bernson made the music and sounds. Reeducated is an immersive 360-degree film. In layperson’s terms, that means the experience takes place all around you and is meant to be viewed in a special headset. You can watch it here, with or without an apparatus, through the New Yorker’s web site or through your Oculus Library. You should watch it before reading this newsletter.

The New Yorker also made a behind-the-scenes video you can watch here. What follows is more or less an expansion of that featurette, going into (much) greater detail about the challenges and advantages of V.R.—from my point of view, anyway. It’s all my thoughts on working in the medium and all the stuff I wish I’d known before we started.

(Subscribers: This newsletter is too large to display in your email, so click through to read it in full in your browser.)

First, what’s going on with the film?

Reeducated premiered this March at SXSW and will go on to screen in two other festivals this June. First, a European premiere at the NewImages Festival, a Paris-based V.R. festival. This year, NewImages has joined forces with Cannes XR and Tribeca Festival to offer a co-curated selection of XR projects called the Forum des Images, which is where you can find our project if you attend any of the three events. After that, the film goes to Hamburg for the VRHAM! festival.

O.K., on to the main event…

What is virtual reality?

Writers are often thinking about narrative, and I mean this question in a narrative, not a literal or technological, sense. I assume you already know that virtual reality describes a cluster of technologies that allows a user to experience a virtual world, primarily through a vision-filling headset with a “stereoscopic” screen that confers a sense of depth by showing a slightly different image to each eye. In some cases, there are other features, like spatially oriented audio to create an aural sense of emplacement, or motion detectors to allow a user to move a virtual body through a virtual space while the physical body moves in physical space. (A high-end variant of this last one is known in the industry as “6DOF”—Six Degrees of Freedom.) Whatever the combination of effects, V.R. is an effortful and expensive technology with a lot of non-narrative applications—real estate, PTSD therapy, distance orgies—but here I want to talk about its narrative uses. What is a virtual-reality documentary? What is “immersive” filmmaking?

From my point of view—I can only describe it as an outsider, as a writer and interloper in the field—an immersive narrative tells a story where the action takes place all around you, all at once. It’s tempting to describe V.R. as a film whose screen wraps around you in a 360-degree sphere of light and sound, but after watching a lot of them and making one, I don’t think the analogy to film is as close as it seems at first glance. A film is still bounded by a screen just as a play is bounded by a stage, and this boundedness informs so many of the building blocks of the genre—framing, cuts, camera motion, on- and off-screen divisions—it’s a little deceptive to describe them with the same word.

An immersive film is, to me, closer in its narrative elements to a radio play, in that the experience appears to take place entirely in the mind. There is no screen, because the headset quickly vanishes from your perceptual awareness in a way a film screen never quite does. In a movie theater, I never feel like I’m diegetically inside the film—I might feel “lost” in the story but I don’t duck when a gun is pointed at the audience, as early filmgoers are said to have done—but a V.R. experience tricks the brain quite effectively, even when the surroundings are animated or otherwise fantastic. It is treacherously easy, for example, to make a viewer nauseous if events in the film do not correspond with the brain’s internal sense of place and movement. (I strongly recommend avoiding any films with scenes shot on boats.)

If I look away from the radio, the story keeps going. No matter which way I turn, the V.R. film keeps going, too. The action is unbounded and omnidirectional. As a result, I end up feeling the same way watching a V.R. film as I do listening to a story read out loud: the action is occurring somewhere in the mind, framelessly, and the narrative world is in some sense assembled there, too, by a narrative homunculus.

This realization was finally driven home to me in a paradoxical way, when I was watching some of the other entries at SXSW that were decidedly non-narrative, and that in fact most resembled the experience—I don’t mean this pejoratively—of being inside a crazy screen saver. The experience drew on the sense that my body was situated—often it was kind of floating—in an abstract, psychedelic, space, not mediated through a screen, stage, or page of text.

(One of several memorable little V.R. films I saw at SXSW was Odyssey 1.4.9, a 7-minute short inspired by, and in part built using scenes from, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. This film ingeniously worked to situate the viewer in a position analogous to the never-seen aliens or superior beings of that film, whose relationship to time is entirely different to ours. It worked because of the earlier film’s familiar narrative, of course, which helped me understand the filmmakers’ unstated intentions (I think), but also consciously expanded on Kubrick’s experiments with the language of film, such as the famous millennia-spanning bone-to-satellite cut, using, well, you kind of have to see it.)

I wondered: Why were these projects effective? I decided it was because the films successfully dramatized the fact of my embodiment in whatever world was being created. They weren’t gimmicks, like a lot of V.R. material on YouTube is, inviting you to go BASE jumping or ride the world’s tallest roller coaster. They dramatized features of perception in the same way abstract works of sound and video art do. Here, however, my body and its surroundings served as the plane of experience.

Narrative V.R. is likewise concerned with the viewer’s presence in the perceptual field, but faces other dramatic tasks and challenges, as well. Like immersive live theater—Sleep No More is the breakout example—an immersive film is simultaneously happening all around you, including directly behind you. It’s not only possible that you’ll miss some element of the film, it’s guaranteed. It’s inherent to the form. You won’t see everything in one viewing, and a filmmaker has to take that into account. The viewer needs to have their attention subtly guided to important events that are bounded somewhere within the visual field, and even then they still might miss it because they’re looking somewhere else. For this reason, the filmmaker must create an experience that is satisfying and diverting in all directions, and so, ideally, any narrative momentum should be somehow connected to exploration of the space. To be honest, it’s a highly unliterary form—less War and Peace and more Where’s Waldo. (If I had to compare V.R. to a novel it would be Georges Perec’s Life: A User’s Manual, the great formalist exploration, room by room, of a Parisian apartment building, where the objects in each apartment are the primary engine of narrative movement.)

Finally, as with radio, there are also both cognitive and technological limitations. A radio play is limited in length to the amount of time a person might sit next to a radio, and limited in certain kinds of complexity, too: It’s not really possible for a listener to keep track of two-dozen characters. Likewise, a V.R. film is most obviously limited by the length of time a person can comfortably live inside a helmet. This turns out to be something like 20 or 30 minutes. Although the apparatus does disappear quickly from your awareness when you strap it on, the helmets aren’t weightless. After 30 minutes or so, you feel the weight on your neck, and for me, eye strain becomes a major distraction. For most V.R. films, five to 20 minutes seems to be a sweet spot for frictionless viewing. (Ours is 20.) But, just as there are infinite ways to write a perfect 3-minute pop song, the possibilities are limitless for short-form V.R. films that aspire to art.

Sam has made a number of immersive film projects and came to this one with a lot of wisdom. One guiding principle he brought was that it is extremely easy to overwhelm a viewer in a headset, be it with motion, with information, or with narrative complexity. The sensory experience of being inside a headset is powerful, and there may be a reason many of the most popular 360 videos on YouTube’s dedicated V.R. channel are those that simply place the viewer on a mountaintop or beach, or at a famous world heritage site: the feeling of transportation into a convincing, mimetic world is a major component of the viewer’s experience, no matter the subject. At least in its current maturity as an art form, V.R. is primarily concerned with the dramas of physical space and the viewer’s embodiment within it. That might seem like a limitation. Perec would have called it a constraint.

Why make a V.R. film?

The simplest reason is, because the medium fit the story. This sounds tautological but…it isn’t. It’s the same reason I’ve begun some journalism project only to end up writing an oral history or travelogue. It’s why some ideas become poems and others sonatas. The form of a work of art always emerges in part from the material. The material makes certain demands of emphasis and structure. Beginning, middle, and end show themselves. Events require this framing but not that one, and every positive choice is also a negative one: you’re deciding what not to show and which subjects or context not to include. (An oral history will be light on writerly analysis, for example. A V.R. film will be light on data analysis.) Formal decisions in turn influence the selection and development of material.

As in all other genres, the relationship between form and content in nonfiction is symbiotic and hard to analyze postmortem. But in this case, Sam and I knew from the start we had a story that V.R. could illuminate in ways no other medium could. This is not an admission a writer makes easily, but Sam convinced me, in part by showing me some of his incredible past work.

Reeducated is about an inaccessible, neo-totalitarian space in Xinjiang: “reeducation” camps in popular discourse, or “vocational education and training centers” according to the Chinese government, designed—according to leaked government documents and statements by authorities—for “diseased” minds and for those whose brains need to be “washed clean.” Whatever the name, government sources, critics, and independent journalists all suggest that these centers discipline inmates and instruct them in Chinese language acquisition, Communist Party propaganda, and the dangers of Islam. The government further claims the centers offer vocational and job training, but I have seen little independent evidence of the fact, and all the eyewitnesses I’ve interviewed discount the notion that the camps are primarily designed to empower Xinjiang’s citizens, economically or otherwise.

Sam and I knew each other from living in the same neighborhood in Berlin, and we had often talked about working together. But we were willing to wait for the right project to come along. “It couldn’t be gimmicky or forced,” he recalled. “It had to be the right story for the medium.” In 2019, as we went over my past reporting, we realized much of the the narrative momentum and drama of these stories were connected to the unfamiliar spaces of the camp itself: the look and feel of the cell and classroom; the interactions, both among prisoners and between prisoners and authority figures; the sounds and sensations of incarceration; the feeling of claustrophobia; the moments of interrogation, torture, and alienation in a totalizing space.

The break came on a trip to Kazakhstan that September, when I separately found three men who had been detained in the same camp, at the same time, and asked them to go on the record about their experiences. It seemed to us that V.R. could illuminate their experiences in a unique way. We began to develop an idea for a film built around the painterly reconstruction of these unfamiliar spaces, in a style that would reflect the imbrications and echoes of multiple voices recounting overlapping experiences. We collaborated with the artist Matt Huynh on developing a visual approach. The style of the film’s illustrations and animations owes everything to Matt’s vision.

After we interviewed the three subjects at length, in December 2019 (as described in my previous newsletter), we began to figure out what shared and unshared spaces we would show—cell, classroom, prison yard, border, hospital, solitary pit—and how the voices of the men would conjure those spaces together as a kind of dramatic chorus drawn from our interview recordings. The multiple accounts also allowed us to triangulate, so to speak, our evidence for what these rooms looked like. Interviewing the men separately, we could use one account to fact-check and corroborate the others.

There were other reasons to work in the medium. Within the industry, it is now an eye-rolling cliché to say that V.R. is “an empathy machine,” capable of fostering “empathy toward suffering people, as well as [providing] enjoyable experiences able to attract wider audiences.” V.R. filmmakers may be rightfully sick of hearing this. No artist thinks about their work in strictly therapeutic or practical terms. Most of us want to make work that aspires to more ambiguous qualities of literature and art. (I am certainly sick of hearing fiction defended on the grounds of its pedagogical and psychotherapeutic values: Should we toss out Bernhard and Céline because their works makes me feel misanthropic, world-hating, grim, nauseous, and perverse?)

But there’s no denying that some kind of empathy quotient was one of our considerations during the making of Reeducated. For one thing, I’d been disappointed by the limited reach of my previous work on the subject. I felt, maybe egotistically, but also with the righteous indignation of the freelancer, that the stories I’d published on Xinjiang merited more attention than they’d received. I wondered if the medium might be part of the issue.

I’m not consciously thinking about “empathy enhancement” when I write a story, but it’s a subject that comes up a lot in research surrounding virtual reality and journalism, and both Sam and I recognized the value of taking viewers “there.” And, for whatever it’s worth, research suggests that V.R. offers a special kind of “thereness.” One study, whose validity I am not qualified to judge, had different groups consume the same journalistic material using different mediums, from print and photo to V.R., and found the following:

Participants who experienced the stories using VR and 360°-video outperformed those who read the same stories using text with pictures, not only on such presence-related outcomes as being-there, interaction, and realism, but also on perceived source credibility, story-sharing intention, and feelings of empathy. Moreover, we found that senses of being-there, interaction, and realism mediated the relationship between storytelling medium and reader perceptions of credibility, story recall, and story-sharing intention.

A third reason we chose the medium is that nothing quite like it had ever been done before. That’s not to say immersive narrative journalism a new concept. There are lots of documentaries and interactive projects that use V.R. to make inaccessible spaces come to life. One that I really admire is “Home After War,” a room-scale interactive experience guided by an Iraqi father who returns to his home in Fallujah. We were also inspired by the work of Forensic Architecture, several of whose members are visual and multimedia artists. (I’ve previously written about an affiliate artist, Lawrence Abu Hamden.) Forensic Architecture often uses unorthodox artistic interventions to produce important research on asymmetrical conflict and revolution, turning the surveillance technologies of oppressive states back onto those who typically wield them.

But neither I (a total novice) nor Sam (who has seen a lot of it) had seen V.R. used in quite the way we planned it, to reconstruct an inaccessible space with such thoroughgoing attention to eyewitness detail and multiple eyewitness accounts, and to moreover create every surface and object by hand, using ink and pen drawings. Our project would combine the immersive and empathetic qualities of films like Home After War with the journalistic diligence of Forensic Architecture’s work. We would also pair the film with a long-form article I’d write that would tell a panoramic story of life in Xinjiang. This combination felt unique, and we hoped it could be uniquely affecting.

The project seemed unique among coverage of Xinjiang, too. By the time we began to develop the ideas that became Reeducated and “Inside Xinjiang’s Prison State,” I knew the kinds of nonfiction projects that were out there. I also knew what wasn’t out there. There were many important news-style features based on leaked documents and satellite imagery. There were several firsthand accounts of detention, too. But there were no really ambitious magazine stories based on these accounts (some others have since appeared), and what narratives did exist were somewhat skinny, often relying on a single survivor or eyewitness. I knew we had the material to make something especially ambitious, using multiple witnesses, documents, maps, and a polyphonic approach, while still focusing on the narratives of everyday Uyghur and Kazakh people—from farmers to truck drivers, nurses, and businessmen—who had been caught in the state’s net. We approached The New Yorker that October.

From the start, we knew there would be downsides to making a V.R. film, compared to a conventional animation or just an “interactive” (i.e. scrolly) article. V.R. is a niche product and we knew relatively few people would be able to see it as intended. We were expending a lot of effort and money on effects that would not be perceptible to most of our audience. Not many people have a headset, and while it’s technically possible to watch the film on a smart phone or in a web browser, the effect is much diminished. It’s sort of like making a painting you know will sit forever in a jealously guarded private collection, consumed by the public mainly through cheap black-and-white photocopies. (I’ve also compared it to watching a film with the sound off—there is an entire dimension of experience that is lost, one that contains not just information but style, tone, and mood.) Our editors at The New Yorker were keenly aware of these limitations, even as they were really excited by the project.

We still hoped the film would generate buzz beyond the V.R. world by virtue of its novelty and its own artistic and narrative merits, and that together with the interactive article, we would reach a wider audience than straightforward news reports—without sacrificing the value of the reporting itself. It’s to The New Yorker’s credit that there’s not really any other publication that could have swallowed all of this, or helped us bring this vision into reality. And it’s to the immense credit of the organizations who helped to fund the reporting and production costs, which expanded dizzyingly over the summer as the actual gruntwork caught up to our high ambitions: the Pulitzer Center, Eyebeam, and the Online News Association. Their support helped us feel like our vision wasn’t totally off-base, and that the project could serve as a proof-of-concept for innovative works of immersive journalism on other subjects.

How did we make it?

Following our reporting, as I drafted the article while under lockdown in Germany during the spring and summer of 2020, Matt began to draw the environments that would become stage-like sets for the film’s animations: a kind of animated theater in the round. He made a storyboard based on a loose narrative shape we all agreed on.

While he worked, Sam and I began developing a script based on our transcribed interviews, paring down many hours of tape to—after many, many drafts—around 100 lines of dialogue. We brought on Nicholas Rubin, an animator and technical director with Dirt Empire, to make Huynh’s drawn environments into diorama-like sets in three dimensions; Rubin and a small team of animators and assistants were charged with assembling thousands of Matt’s perspectival drawings into 360-degree space, lighting it, adding textures and effects, and rendering the whole. Reeducated, Nick told me, is the most technically difficult project he has ever worked on.

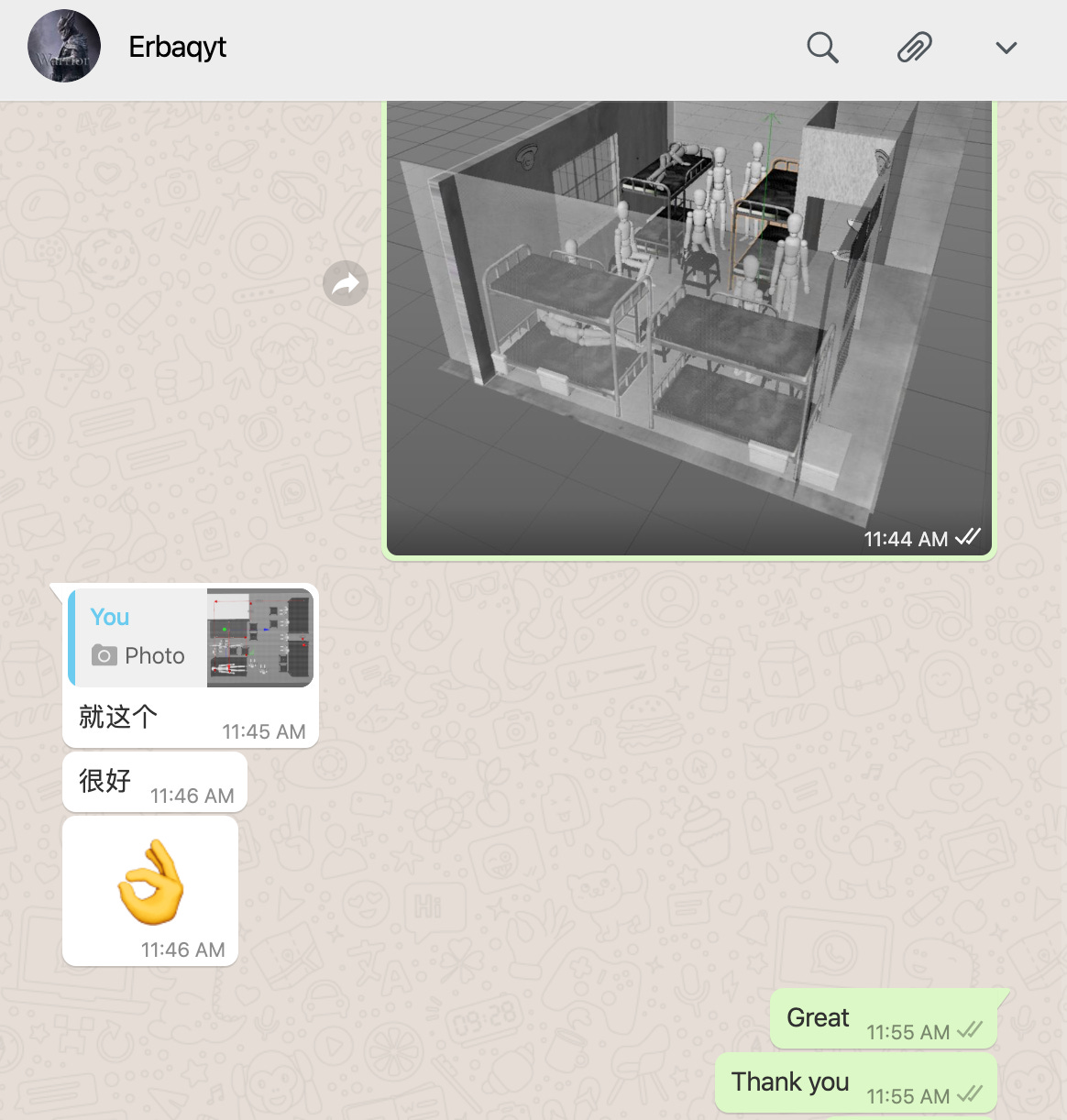

Throughout the process, I was in touch with each of the film’s subjects, asking them—often to the point of irritation—to clarify and confirm details or add context. I’ll admit we became obsessed with the accuracy of certain details in ways that a fully animated project seems to encourage. Matt was drawing every part of this universe, so every part, from the video cameras to barbed wire, became something we could potentially get right or wrong. It was entirely in our hands. We wanted to get it right. To confirm the accuracy of each detail—from the model of surveillance cameras to the view through the windows to the shapes of inmates’ bunk beds—we did our own research and I sent drafts of Matt’s drawings to our subjects via WhatsApp.

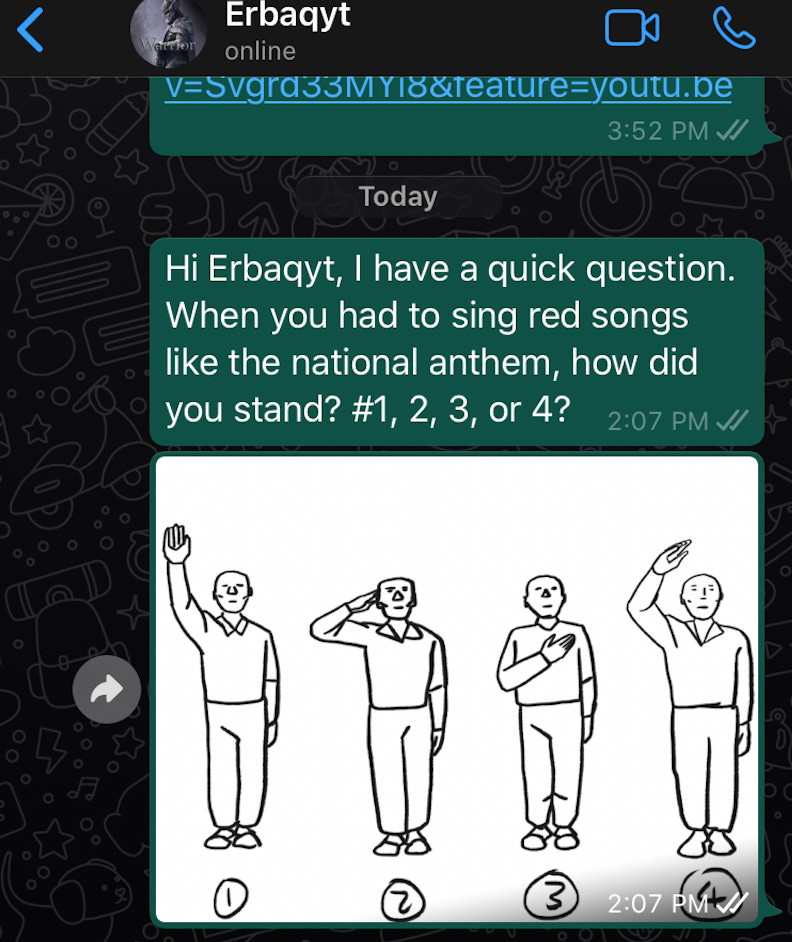

For example, when the subjects sang the national anthem, Matt realized he wasn’t sure how they might stand. He asked me but I was ignorant. Was it different in China than in the U.S.? Hand on heart? Salute? Cursory searches on Google turned up all kinds of information and different stances depending on the group, whether military or civilian, and the situation. (For that matter, I wasn’t sure what the different stances and contexts were for my own country—military vs. baseball game vs. school assembly!) I asked a couple of our collaborators who were themselves from Xinjiang, but they weren’t sure what to do, either. Finally, I had Matt draw several options and I asked the men themselves:

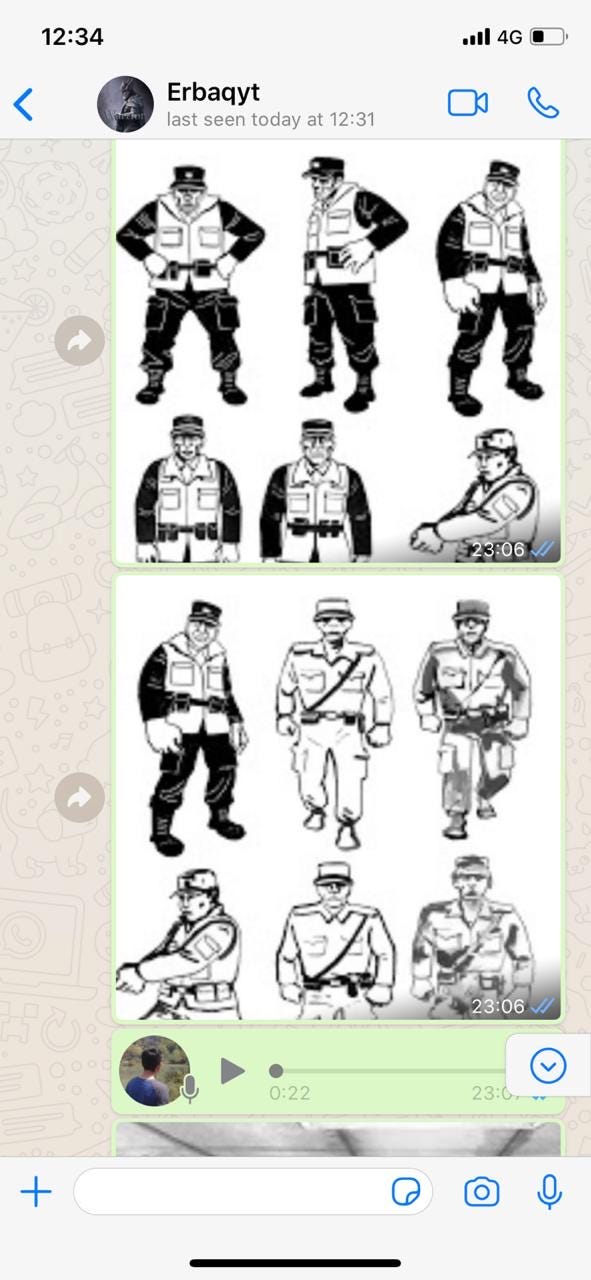

This proved to be an effective way to go about things. Later on, Matt had several source images for police and security officers in Xinjiang, and we wanted to make sure his drawings were accurate. Again, we ended up going to our sources:

Did these little details really matter in an animated film? Would a viewer notice or care? We thought so. The quest for verisimilitude isn’t just a matter of feeling correct. I think it bleeds into every part of a project. A commitment to accuracy was also a commitment to precision, not just in the facts but in narrative and aesthetic concerns. For a subject like Xinjiang, where every fact is contested and every claim processed through an ideological lens, it felt all the more important to be precise. As a result, everything—the drawings, the script, the sound—became more precise, sharper.

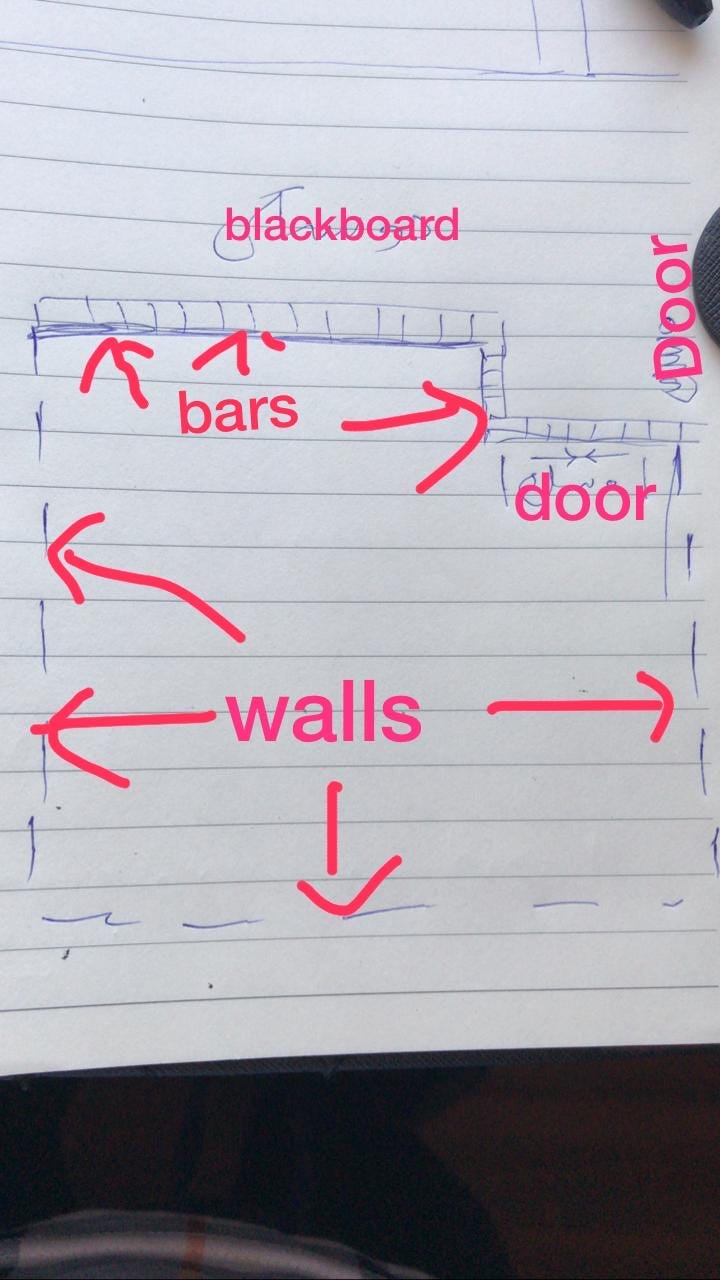

Our greatest concern was for the spaces themselves. During our initial interviews, we focused to a fault on the size and contents of each room where the men spent any time. We had our subjects draw the floor plans of each space. We also had them imagine they were standing in the middle of each room, then laboriously describe what they saw in all four directions. What could they see through the windows? How many people were around them? What was the light like? What could they hear? We explained why we needed to be so precise; but they already understood. It was important to get right. Erbaqyt, in particular, was excited by our unusual interest in concrete, material details. It was also vital that we’d brought Matt on our reporting trip. He anticipated a lot of the questions he might have later, when he was drawing, and so was able to ask the subjects directly.

Here is a sketch one interview subject made of the classroom:

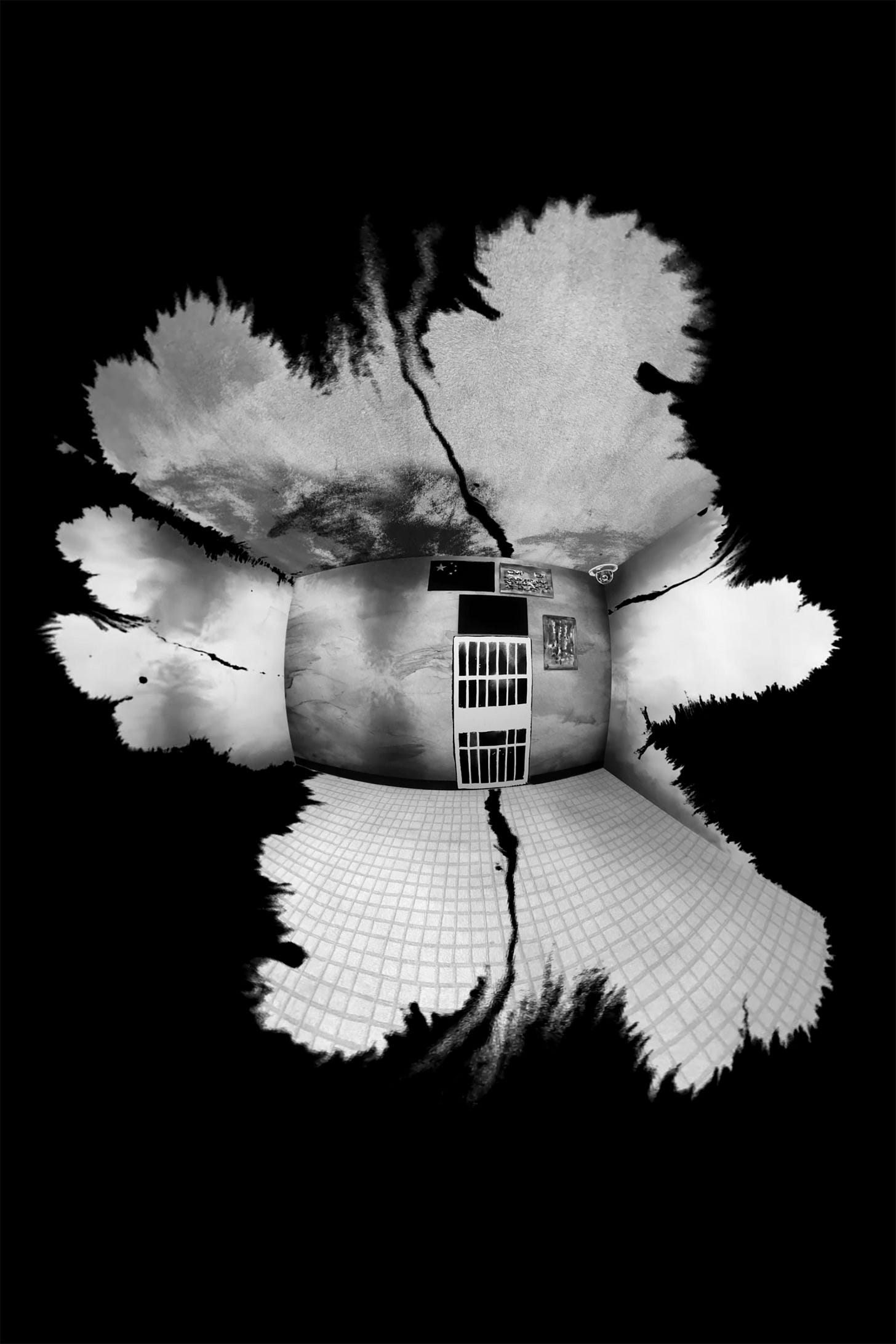

We used these sketches to ask more detailed questions, not just about architecture and geography, but about the events that took place there. Matt used dozens of sketches like the one above to build the initial environments for the film. His early drafts were simple sketches designed to work in a 360 browser environment like YouTube. Although you can’t really tell from these gifs, the cell below is essentially drawn on the inner surfaces of a six-sided box:

Next, Matt began to people the cell with prisoners:

Finally, he added his signature ink drawing style, which, for me, was when the room started to feel meaningful. Characters began to emerge. The space became something you wanted to explore. Getting to this stage was a great relief for all of us. Up until then, the process, from reporting to storyboarding and scriptwriting, had felt risky. We weren’t quite sure what we were doing. None of us had made anything like this before, and in a sense we were all working left-handed (or in my case right-handed) in mediums we weren’t familiar with. When we saw the room below, we realized the film was going to work.

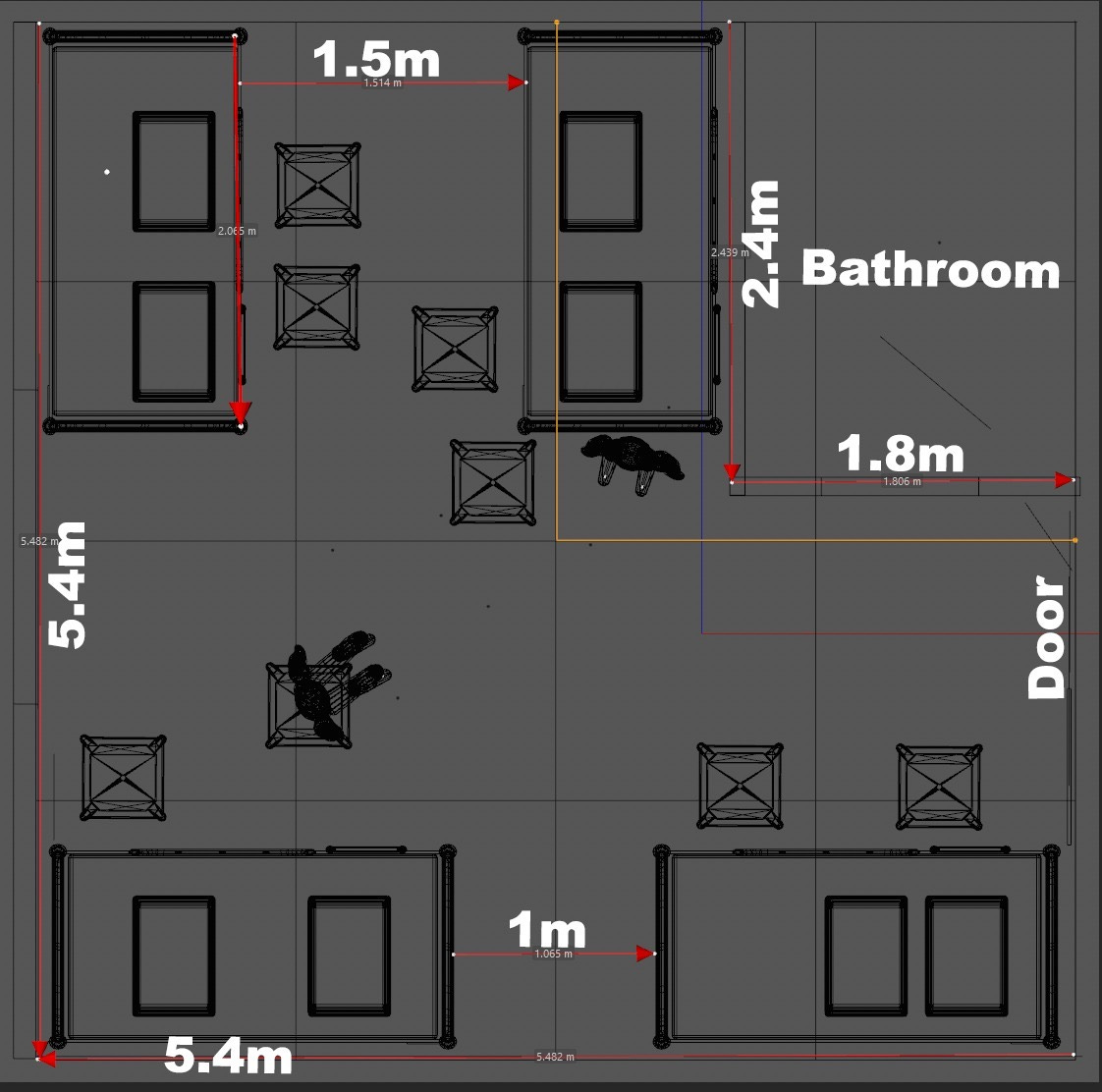

Once we started working with Nick, a technical and 3D mastermind, we were able to scale up our ambitions a great deal. The above sketches are monoscopic—they look fine in a browser but have no depth. The illusion of dimensionality would fall apart in a headset, and you could never stand convincingly inside the middle of one of the above 360 spaces. For a room to feel real, while maintaining the ink-on-paper aesthetic and Matt’s hand-drawn style that had come to define the story, we would have to build it with 3D models and then make it look like a 2D drawing, applying the flat drawings as you might in a shoebox diorama. That was Nick’s great challenge and throughout the process he performed a lot of technical wizardry to make it look “real,” which is to say consistent. Like an architect planning an actual building, he began by creating floorpans for each space based on the information we had from our subjects and (to a significantly lesser degree) other interviews and known information about other camps in Xinjiang. Here’s the floor plan for the cell shared by Erbaqyt and Orynbek, where the first half of the film takes place:

Matt’s early experiments now became early 3D spaces on Nick’s computers, each surface and object of which would eventually be replaced by Matt’s perspectival drawings. We weren’t yet looking at a film in headset, but we were now moving from something like two-and-a-half to properly three dimensions.

We didn’t have time to draw everything and then have Nick build 3D sets to match. Matt and Nick had to work simultaneously, Nick building scenes with temporary assets in Cinema 4D (and later compositing the final animations in Adobe After Effects) while Matt hand-drew and scanned new illustrations and animations. Nick described the process in more detail in an interview with XRMust:

We were essentially building the scenes - lighting, editing and designing - all at the same time and working in tandem with rough cut edits from Sam to build the piece organically from the very beginning. This allowed for creative and aesthetic exploration almost the entire time but it is not the way a normal CG animation is produced and is incredibly time consuming.

Time consuming is an understatement. It was brutally slow work. And every time we made a new major change or a new draft, we had to check details with our sources to make sure we were right on the spaces and objects, the size and arrangements of each room.

We were constantly fine-tuning the rooms, going back to the interviews for details and self-correcting, discussing details in Slack and giving Nick notes. We wanted to make sure the cameras were in the right place—

—and that the posters in the cell were accurate.

As Sam and I worked further on the script, we began to figure out what events we would want to depict, and Matt began to sketch the animations: sleeping, eating, watching TV, studying. Again, Sam focused our efforts on a narrative that would require the viewer to explore the spaces we were building. In a conventional film, we might have focused on one person’s story, on dialogue between characters, or something else, but here the material and the medium were driving different narrative decisions than those I was used to in print journalism. I can remember him cutting huge swaths of my proposed dialogue, promising me that I would thank him later for leaving in breathing room. There were lines I thought were so poignant and heartbreaking I hated to lose them—I never would have stood for it in a piece of writing—but Sam claimed they cluttered the scene, and that a viewer couldn’t both take in dialogue and look around an unfamiliar environment. You had to build in a lot of silence, giving the viewer a lot of space. (He was right, of course. As soon as we began assembling drafts that I could watch inside a V.R. headset, it was clear the cuts had been needed.)

Occasionally we added material at this stage, too, and in one or two cases I petitioned to insert a new scene late in the process. One was a short section where guards come into the cell to search for contraband. We knew this activity happened in the camp each week but hadn’t initially planned to depict it in the film—it would be busy and require a lot of new animations. But, after reviewing an partially animated draft, it was clear that the degree of surveillance in the cell wasn’t yet legible. The guards in the film were not physical presences in the cell; we agreed that we somehow had to show the kind of interference and surveillance the inmates told us they’d constantly felt. “They wouldn’t leave us alone,” Erbaqyt had said. We went back to our interviews, found an appropriate line, and Matt went back to the drawing board to add the new animations.

As this example shows, accuracy wasn’t always a matter of getting the spaces and objects right. It was also about conveying the felt reality of their experiences in an accurate way. A film will always be a reconstruction of reality—how could we demonstrate the feelings of tedium and fear, and of other emotions, which the men felt in the camp? We were conscious, too, about the risks of showing their experiences as too miserable. Although the men were physically tortured, in one case several times, and although two of them had to spend time in solitary confinement and face other indignities, they weren’t beaten and tortured every day, and we didn’t want to suggest otherwise by only showing the most traumatic moments from their time in the camps. And there were grains of truth to the government story: Orynbek, at least, really did receive Chinese language instruction. And sometimes the men did laugh and joke together. We didn't want to produce a misery exploitation film, in other words, that conveyed something that was worse than reality. We tried to choose moments and memories that conveyed the full range of experiences they had described: not just torture and misery but moments of levity and of brotherhood, too.

What is (and isn’t) possible in 360?

I guess one thing I want to emphasize for anyone working in a new medium like this is the extent to which a seemingly simple formal decision can cascade into a greater set of possibilities and challenges. I think this happens no matter what the form—whether you’re writing a blog post or a conventional piece of longform journalism—but we may not really notice it unless the medium is new to us.

The key narrative decision we made early in the process is so obvious it’s easy to miss. It was to use multiple narrators to describe environments that would then appear, as though painted by memory, all around the viewer, in 360-degree space. The viewer would be stationary and locked in place as scenes from the men’s months of imprisonment played around them. The spaces would even be physically painted or conjured in response to the spoken memories, using inky effects that mimicked Matt’s brushwork.

Once we made it, this central narrative decision led to an avalanche of others—almost every subsequent decision in the film. Some of those decisions could be viewed as drawbacks, others as ideas we would not have come to on our own accord without the constraints we’d given ourselves.

I’ll stick to one example. In light of the decision to construct the camps based on the memories of three interview subjects, it became a rock-bottom imperative for me that we hear the real voices of the subjects in the film—and, by extension, hearing their emotions, vocal tics, and other modulations. In my mind, the voices subtly convey to the viewer that this is a documentary, not a fictionalization: these events happened to these men, and now they are talking (or singing) to you, making the events come to life in your mind. Among the most frequent pieces of praise we got about the film was the inclusion of Erbaqyt’s singing, a choice we couldn’t have made without the use of their voices throughout.

But a subsequent issue we long struggled with was the question of identifying the speaker in a scene. It wasn’t always easy to tell who in a room was speaking in overdub. The speaker is (with one conscious exception near the end) always present in the scene he is describing, but unless you have a really good ear for Kazakh as well as a really good eye for faces, it’s hard to distinguish among the three voices and figures, especially with both Kazakh and English overdub playing.

Was this a problem? Or was it a narrative choice? Could we change it, and if so, should we? The normal solutions for a filmmaker don’t apply. You can’t “frame” a close-up shot on the speaker as you would in a conventional film to show that a given line is said by, say, Orynbek, and not by his cellmate Erbaqyt. There’s no “framing” to speak of. No “zoom” either. Everything in the environment is present on-screen at all times, just like in life. For writers, illustrators, and filmmakers alike, this limitation is extremely unintuitive. (It was also unintuitive for the very bright folks we worked with at The New Yorker; early on, the editors and producers once or twice asked whether objects or text would be brought into frame, or whether we could zoom in on a subject. I couldn’t blame them, as I often struggled to “think in 360” myself.)

In weekly Zoom meetings, and in long conversations on Slack, the four of us went back and forth over how to resolve the issue. We talked about it for months. Should we use a color to designate the speaker? The same color for all of them? Or should each character have his own designated color, which we could also use to illuminate objects as he conjures them in his memory? Should we instead use a subtle texture or lighting effect? How subtle?

Each possibility came with its own set of drawbacks. A color highlight might be distracting. Moreover, it might interfere with Matt’s stark black-and-white, ink-and-pen style. On the other hand, it was hard to come up with a non-color texture or “boil” (cycling animation) that would telegraph clearly to the viewer that a character was speaking. It was maddening to figure out how to make an effect signify in a particular way without overdoing it.

The problem boiled down to a question of which world this film lived in. Was it a work of art or a work of journalism? Personally, I went back and forth on the importance of identifying the speaker; at times I felt it was important to know, even at the expense of aesthetic concerns, especially because the relationship between two characters, Erbaqyt and Orynbek, lies in some sense at the heart of the narrative. I also wondered whether the source of a line of dialogue might be journalistically important for the viewer to know. Then, reviewing a test, I would change my mind and say that it didn’t matter, and that the three of them spoke with a kind of collective voice, a first-person plural like Svetlana Alexievich’s “choruses” that only occasionally blossomed into individuality. In these moments, the relationships and sense of brotherhood were successfully conveyed collectively. I think Sam, Matt, and Nick went back and forth in a similar way.

Elsewhere, we were relying on black-and-white animation to produce particular expressionistic effects. Especially at moments when the voice-over goes to a place of solitude and subjective experience, Sam had come up with a variety of visual ideas for making those moments pop, many of them drawn from film noir and German expressionism, cleverly applied by Nick to a 360-degree environment. How would we maintain that effect with new colors added?

This was a somewhat abstracted concern for me, the reporter, but each new idea spawned drafts of drawings by Matt and rendered environments by Sam, Nick and Nick’s team of animators—dozens if not hundreds of hours of work to think through one of our many ongoing narrative problems. In the end, the chorus won out, and speakers and the objects they describe are distinguished only contextually in the film, not by color or special texture effect. I tend to think it was the right decision, but it wasn’t an easy one, and it wouldn’t have come up in any other medium.

At the same time, the medium also created interesting opportunities to play with certain animation effects and their relationship to time and the suspension of disbelief in V.R., a process Matt describes beautifully in an interview with XRMust:

I had to be deliberate with how motion was used to direct the attention of a viewer. Instead of constant motion, I arrived at dioramas with selective motion along the spectrum of perfectly still illustrations, boils, loops and unique actions.

A boil [a small, enlivening cyclical animation] directs the viewer primarily to a character, pulsing with their own thoughts and will, but a boil is a quick read because there’s no new information. A loop [a cyclical animation containing concrete action] draws attention primarily to an action like singing, reading or sleeping. If an action is too idiosyncratic, the conceit of the dreamy pace of remembrance is broken. A distinct action places the viewer in a singular moment and pace of life that too closely approximates the novelty of experiences outside the headset. We risk waking the viewer from the suspension of time we hope to create to explore a fabricated environment that the viewer’s transported into. And of course, all these rules were ready to be broken for effect. For instance, an inanimate object may be given animation to emphasise the regime’s power in a setting where everyone else is stripped of autonomy and too afraid to move.

The Transfer

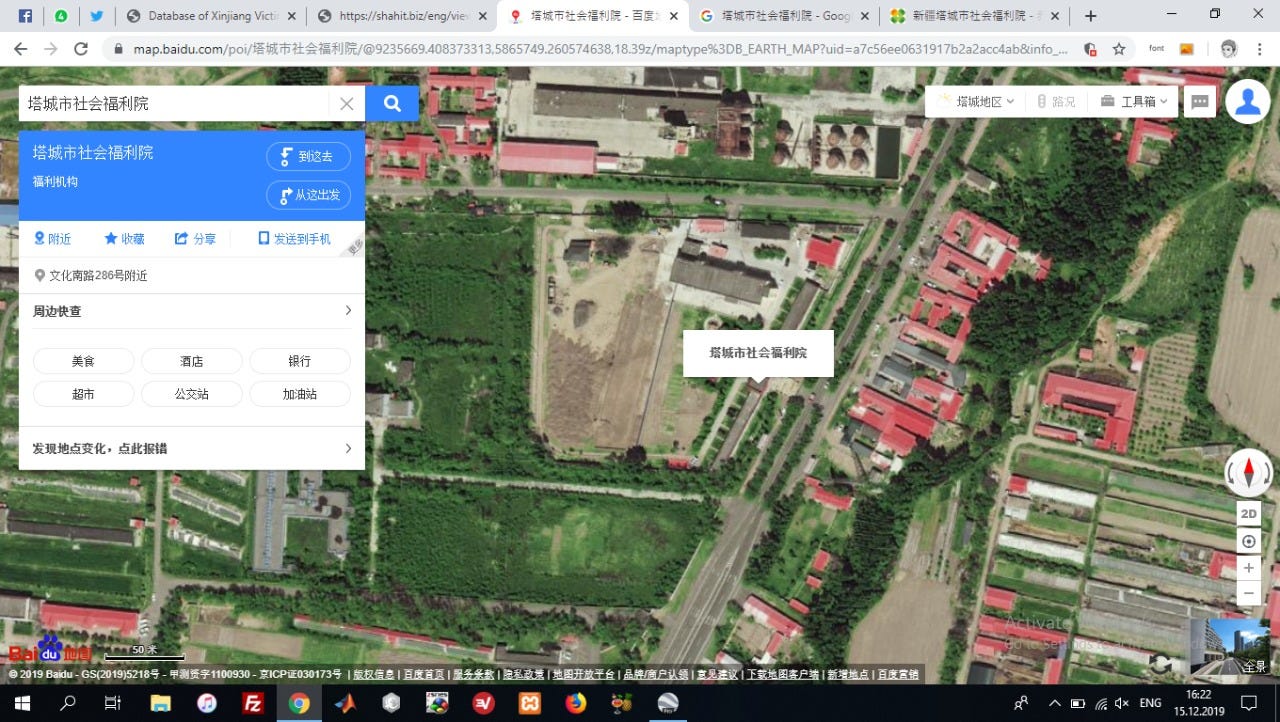

One especially complicated scene was set outdoors. It depicted the day, in April 2018, when hundreds of prisoners at the Tacheng camp were taken out to a yard and transferred to a newly built camp a few miles away. All three men had described the transfer in detail during our interviews, their memories of the space corroborated by satellite images and photographs discovered by the scholar Gene Bunin on a since-removed article on the Chinese media app WeChat.

Here’s what a satellite view of the camp looks like. (As described in my reporting, the camp, a former retirement home, grew significantly during the period the film and article take place, from 2017 to late 2018.)

Here’s another view, using different satellite imagery from a different month, with the yard area now highlighted in red. To set a scene here, we had to figure out what this space looked like on the ground.

The scene proved far more complex than the 300-square-foot cell where the first half of the film takes place. Part of the complexity came out of our desire to maintain fidelity to these images, which required us to transpose a two-dimensional bird’s-eye view of the camp yard into a three-dimensional view on the ground. It helped a little that we had photos of what the camp looked like before the detention drive, when it was still a retirement home:

But there was still a lot of guesswork and trial and error.

To get it right, we re-interviewed each source while making the reconstruction. I asked more annoying questions about details like their restraints and positioning in the yard. I was a little worried about the tact of forcing the subjects to return so often to these traumatizing memories. Was I needlessly retraumetizing victims for the sake of stuff that wasn’t so important? I tried to tread lightly, and to give our sources the chance to decline to revisit those moments. But the subjects were resilient and uncomplaining, and even, sometimes, insistent. They believed in the project too, and wanted us to nail the details.

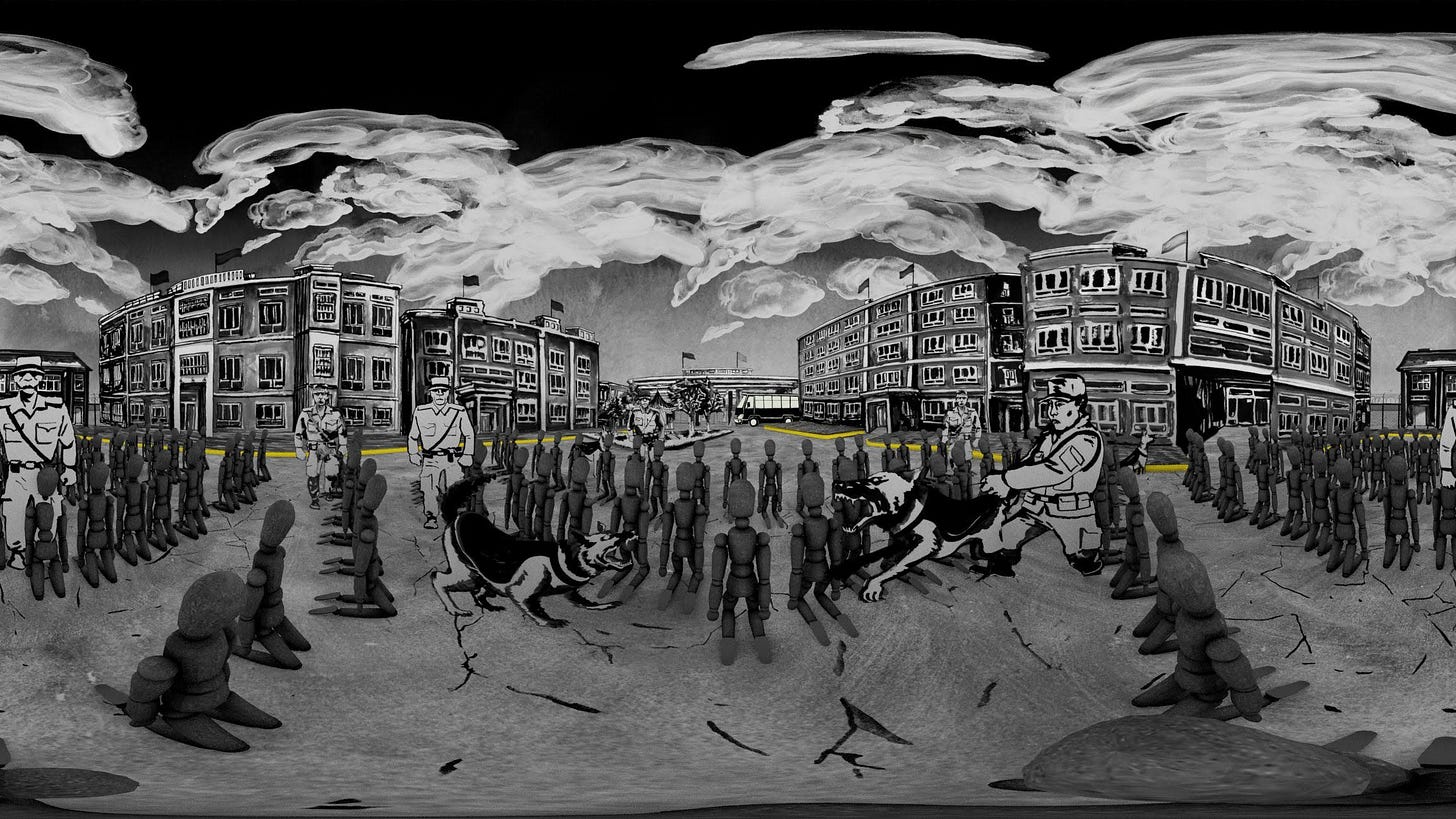

The transfer they described had involved hundreds of prisoners, a huge illustration and animation task. Matt and Nick broke them down into groups to help simplify the problems of perspective that come from building flat 2D drawings into a 3D environment. Ultimately, every figure had to be drawn and, in most cases, animated.

The process was slow, and I was amazed at how Matt was able to examine his work in a headset and then make revisions to the figure to correct the perspective on a piece of paper. It reminded me of early Renaissance painters using cameras obscura to nail down linear perspectival drawing. (And I wouldn’t be surprised if, some day in the future, we look back at V.R. as a similarly revolutionary technology in the history of perspectival art.)

But some problems were more basic. One early rendering of the environment (below) didn’t have the yard or position of buildings, gate, and buses, quite right, and our sources corrected us. Matt redrew the scene.

At some point, we realized there were a lot of similarities between the scene we were depicting and a leaked aerial video of a prisoner transfer elsewhere in Xinjiang. Here, too, prisoners were shacked in pairs and surrounded by a number of security officers.

We were intrigued by the similarities, but didn’t want our work to be unduly influenced by a different event that had taken place in a different part of the region. We discussed the similarities and differences with our subjects. They pointed out they hadn’t been made to sit in the same way, and the restraints were a little different. And there was the terrifying presence of police dogs at the transfer in Tacheng, which Amanzhan and Orynbek both had found traumatic. But there were some similarities that helped us, too; we hadn’t realized how many guards such a transfer might involve, and our sources confirmed we’d been underestimating them in early renderings.

The medium itself again introduced further complexity. The transfer scene was the climax of the film, a moment of quiet horror, and we didn’t want to overwhelm the viewer. Early drafts, in which most of the figures were animated with “boils,” were too busy and distracting, even if they were at the same time more “realistic” in terms of movement. We went through several painstaking drafts and camera positions—each requiring new animations—to make the yard both immediately legible and visually striking. In the end, even Matt’s animations were mostly removed in favor of still figures, the better to make the space easy to grasp. Matt was again “deliberate about what movement would be distracting or instructive in directing a viewer through the scene.” Chinese flags flutter, but the prisoners are still.

Final Touches

As the film progressed, it was satisfying to see drafts that came close to approximating a finished product, but it wasn’t until we started incorporating sound and music, nearly a year into production, that it began to feel like a real film.

Working in San Francisco (and rising early for our Zoom calls, which always spanned at least three continents), our composer and sound designer, Jon Bernson, made field recordings in isolated industrial spaces to polish the film’s environments. To capture the feeling of the prisoner transfer in the mostly silent yard, he drove out to Treasure Island, a former nuclear-training site in the San Francisco Bay, to record among abandoned concrete buildings. Later, in his studio, he colored the scene with the sounds of moving bodies and guard dogs, and painstakingly anchored each noise to a location in space using a technology known as ambisonic audio whose application to virtual reality is still in its infancy.

All of this work helped to make the transfer scene feel real and effective inside a headset, to hopefully convey some small fraction of the fear and uncertainty the subjects themselves felt. Collectively, we devoted thousands of hours and scores of illustrations to the scene. In the final cut, it lasts thirty-eight seconds.

On another film, it might have been easy to get lost in the technical challenges or become frustrated by the work involved, exponentially more work than any of us had imagined when we started out. As I often point out about freelance journalism as a whole, this is not work that pays fairly. It is all-consuming, difficult, and mostly without material reward. And as much work as it was for me, it was many, many more hours for Sam, Matt, Nick, and Nick’s team, solving the project’s many technical challenges.

But the subject matter of Reeducated provided constant reminders of why we had chosen this approach in the first place. V.R. allowed us to situate viewers in an immersive environment that approximated the spaces of one of Xinjiang’s actual existing camps, making visceral the feelings of isolation and despair that are central to eyewitness accounts like Amanzhan’s, Orynbek’s, and Erbaqyt’s. These effects can’t be conveyed through satellite images or the slapdash computer animations that typically accompany daily news accounts. A film like this isn’t meant to replace hard news, leaked reports, or other kinds of investigations. (And I think it’s important the film had a companion piece of writing online.)

But I also think it’s an important to give viewers and readers narratives that center on individual voices and experiences, not just on population data and satellite images. Over the past couple years of working on Xinjiang, I’ve often thought about great, canonical works of witness, like Alexievich’s Voices from Chernobyl or Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah. In these works, the survivor’s voice is its own category of information, untransferable and unique.

Final thoughts

Once the film came out, there were several pleasant surprises. It was especially gratifying to hear from several family members of the disappeared inside Xinjiang. This wasn’t an easy film for them to watch, a few of them told me, but they were glad to have an account of the experience of detention that they could connect to their loved ones, no matter how grim, and to have something to show others, to say, “look at what’s happening.” Any information from inside the camps was better than none.

I was especially proud that we produced a Kazakh-language version of the film for viewers inside Kazakhstan, working with a journalist, Asqat Yerkimbay, who also recorded the English-language overdubs with Kazakh actors. It was important to me that we make the project available to the film’s subjects and to an audience that most deserves high-quality reporting on Xinjiang, but that for political reasons rarely gets it. I worry about “extractive journalism” that mines a place for stories but doesn’t serve the community being written about, and on past trips to Kazakhstan I’ve felt badly about the “arrangement” that prevails among Western journalist, local fixer, and source. It took some convincing, but The New Yorker agreed to come out with a Kazakh-only film simultaneously with the English version. I have tried in the past to convince editors of the importance of such translations, but this is the first time I’ve been successful, and I’m grateful to the magazine for enabling it.

I was also surprised at how much I enjoyed collaborating on a reporting project as a team. I’m used to working alone or with a photographer. Either way, I’m accustomed to making most of these aesthetic, narrative, and reporting decisions on my own, and later confirming or adjusting those decisions with an editor. I felt some trepidation about sharing creative roles, but I shouldn’t have worried. On top of everyone’s formidable talents, the chemistry felt special. Everyone brought good ideas each week, and everyone had the qualities I most admire in creative people: perfectionism, diligence, and the ability to jettison unworkable ideas and mistakes and move on swiftly. Everyone was possessed, in other words, of the underpraised quality described by the narrator of Norman Rush’s Mating: “The celerity with which people recognize something is spilt milk is a main measure of their rationality.” Conflicts never felt insoluble or bitter. Everyone was working with the same sense of purpose.

I’d also been worried what the film’s three subjects would say about the final project. Although we had consulted with them about factual details and showed them small clips here and there, and although a fact checker from The New Yorker went over all of the events depicted, none of the subjects knew how we’d decided to approach the material, what tone we took, what lines we used. And I was nervous we would somehow get some important detail wrong. When the film came out, the positive responses they had were a tremendous relief. “It seemed to me I saw the real, original camp,” one of them told me in a WhatsApp message after seeing the film. “I’m a little bit astonished. You made the environment—what it really looks like—it’s like you were there!”

Recommended Reading

This month’s recommendations come from Madeleine Schwartz, a Paris-based writer, journalist, and editor. Madeleine is the brains behind The Ballot, an online journal of international politics where I’m a contributing editor. (Our latest piece is an interview she conducted with Palestinian journalist Hazem Balousha reporting from Gaza. Read it here.) Madeleine also writes for the New York Review of Books, Harper’s, and The New Yorker, among other places. One of my favorite recent pieces of her is a brilliant panoramic report from the U.S. immigration courts on the Mexican border. You owe it to yourself to read it, here.

Madeleine writes:

Recently, I've found myself frustrated with the format of "longform" reporting—its focus on turning people into "characters," the way in which the writer tries to erase his own opinions while engineering scenarios that magically conform to pre-existing notions. We're often told that we live in a great era for reporting, but I find many magazine articles sound oddly similar—life moulded to suit narrative.

Reading older works of nonfiction, I've been particularly drawn to books which use the diary form to create polyphonic records of world events. Two stand out. The first is Walter Kempowski's majestic Swan Song 1945, a “collective diary” through the end of Nazi Germany. Kempowski collected hundreds of entries from the weeks leading up to German surrender--Hitler's in there, as is Thomas Mann, but also a Red Army soldier who talks about his inability to seduce Czech women. Journal à Quatre Mains [Four-handed Diary] the collective war journal of sisters Benoîte and Flora Groult, takes up this project on a domestic scale. The Groults lived through the war in France as teens; both became journalists and feminist activists in the 1960s and 70s. Thinking back on our "historic" year of 2020 (already the subject of so many retrospectives), I recognized their fear, their confusion and their annoyance that despite the world falling apart, teachers still expected them to do their homework.

I share Madeleine’s frustration, and like her often ask myself why we have come to venerate a particular framework for “longform” reporting that often strikes me as dull, limiting, and duplicitous. Is it because readers are too distracted to be trusted with a narrative challenge? Is it because longform reporting is now merely an unprofitable content grinder for the real narrative object, TV/film options and podcast series? Anyway, thanks for these lozenges, Madeleine.

If by some chance you’re in Barcelona next week, I’ll be speaking about my reporting on Xinjiang with Manel Ollé for the annual Orwell Day event held by the Center for Contemporary Culture in Barcelona (CCCB) on May 31. Until next time—

xo

Ben