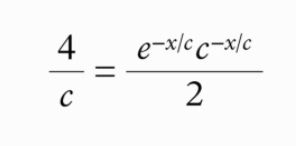

is the sine curve that describes Mayon, the stratovolcano whose slopes form the most regular cone in the natural world. (Let c = 8.6 millimeters.) It was somewhere to our south, at the tip of the island of Luzon, glowing at night with a bulb of magma in its mouth. Mayon is the most active volcano in the Philippines. Around its base are densely populated towns whose inhabitants do not frighten easily. The last major eruption, in 1993, killed seventy-nine people and forced nearly a thousand times as many to flee their homes, as lava and mudflows coursed down the mountain’s dozens of ravines like puddled steel in a smeltery. It has since erupted in 1999, 2000, 2006, 2009, 2013 (a sudden phreatic explosion that killed four mountain climbers from Europe and their Filipino guide), 2014 and 2018. Mayon smoldered and glowed but did not erupt the season of our arrival in Manila. Taal erupted instead.

We were rooming on a street of flowerpot-lined churches in Poblacion, the old market center of Makati, where one evening the parked jeepneys were discovered coated in silken film. A sign appeared in the hotel lobby: the roof deck is closed until further notice due to ashfall. Forty miles to the south, fumaroles sent up curtains of white smoke around Taal’s caldera that returned to earth as damp, unassuming dust on cafe tables as far north as Quezon City. It was our introduction to a sight that would become routine three months later: a city of masked faces. We went looking for a pair of the recommended N95 face masks. They were sold out everywhere.

The volcanic warning level was raised to four out of a possible five. Carleen looked up the chart on her phone at breakfast. ‘Level four means a hazardous eruption is imminent,’ she said, using the same tone of voice with which she had earlier pointed out that a museum on our itinerary was closed for the day. The slopes of the caldera were beginning to inflate like earthen lungs as magma pressed up against surface rock. Color photographs around Batangas showed an ash-desaturated landscape, with roads, crops, cars and houses cast fuzzily in monochrome silver. Lapilli – volcanic cinders as large as billiard balls – fell on houses in villages around Taal Lake. The government evacuated 20,000 people, and eventually more than 100,000 were displaced, many of them farmers living off the rich volcanic soil. Left with no caretakers, their livestock began to starve to death.

At least one Luzon resident was not cowed. ‘I will eat that ashfall,’ President Rodrigo Duterte told the nation. ‘I’m even going to pee on Taal, that goddamned volcano.’ Duterte is nothing if not quotable. In defense of the drug war that is his administration’s signature platform, and in which tens of thousands have died, he has compared himself favorably to Adolf Hitler and his slaughtering of drug addicts to the Nazi persecution of Jews. During his 2016 presidential campaign – unofficial slogan: ‘Kill the criminals!’ – Duterte boasted that, once he was elected, funeral parlors would be overwhelmed by business and the fish in Manila Bay would grow fat on the flesh of 100,000 Filipino corpses. He has since enjoined citizens to murder their drug-addicted relatives and declared his support for gangs and corrupt officials who target journalists, Indigenous leaders and human rights activists, many of whom are ‘red-tagged’ by government forces as violent communists ahead of their summary execution. At particular risk are land and resource defenders, who have become frequent targets of extrajudicial killings by soldiers, paramilitaries and lone gunmen on motorbikes; in 2018, more such killings took place in the Philippines than anywhere else in the world. Duterte has boasted gleefully of having cultivated this atmosphere of impunity, promising to use his powers to pardon any soldier or police officer accused of human rights abuses, and assuring supporters that, if anyone ever attempts to bring him to legal account for his role in all this mass murder, he will pardon himself.

In the mountains, however, Duterte seemed to have met his match. Not even the president could stop a volcanic eruption, or prevent one from opening a dramatic caesura in the churning chaos of consumption and growth that powers the country’s airports, dams and offshore drilling. Schools and businesses shut down; all flights at Ninoy Aquino were grounded. Against a darkening rim of sky, Duterte’s flamboyant rage felt thin.

A friend in Quezon City sent me a text message: ‘You’ve arrived in disaster season!’ There were earthquakes and a polio outbreak in Mindanao, plus a novel virus in China that seemed at risk of spreading to other countries in Asia. Manila’s notorious traffic, second only to Moscow in its average commute times and rococo fleurs of gridlock, all but disappeared as many of the city’s transplants fled home. Carleen and I left, too. We turned away from Taal and the southern volcanic chain, heading north, toward mountains that for centuries have protected and enclosed.

//

That’s the opening of “The Steepest Places” from the current issue of Granta Magazine. The issue has an equivocating, pandemic-era title—Should We Have Stayed at Home? New Travel Writing—that reflects my and perhaps Granta’s ambivalence about travel writing in 2021. The last time Granta devoted an issue to travel writing, in 1984—shelved dramatically (and clairvoyantly?) between issue 25 (“Murder”) and issue 27 (“Death”)—the contributors included several of my aging or deceased heroes and models of the male-dominated genre: Ryszard Kapuscinski, Amitav Ghosh, Bruce Chatwin, Timothy Garton Ash, and (a satisfying cut for this German resident) Hans Magnus Enzensberger. With a couple exceptions I’m not sure a younger generation has picked up where they left things. There’s something intriguingly anachronistic about a travel writing issue, not only because of the pandemic.

Well, it was humbling anyway to be asked to contribute to Granta’s third volume of travelogues, even if I don’t really consider myself a proper travel writer—I’ve never complained publicly about a bathroom, for one thing—because the issue is very good, not at all male-dominated, and edited by Will Atkins, a great travel writer (shall we just say great writer?) himself, one who removed several infelicities and errors from my work. I wouldn’t even describe it as a dream to have an essay in Granta—my dreams are less ambitious.

A little subscribers-only behind-the-scenes: I cribbed the essay’s title from a line in the four-volume memoirs of the Hungarian Baron de Tott, who traveled across the Ottoman Empire. The quote—“The steepest places have at all times been the asylum of liberty”—was immortalized for me in a passage on mountains in Braudel’s The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Phillip the Second, a book I dipped into a lot this year. The passage runs:

'The steepest places have been at all times the asylum of liberty', writes the learned Baron de Tott in his Memoirs. 'In travelling along the coast of Syria, we see despotism extending itself over all the flat country and its progress stopt towards the mountains, at the first rock, at the first defile, that is easy of defence; whilst the Curdi, the Drusi, and the Mutuali, masters of the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon, constantly preserve their independence'. A poor thing was Turkish despotism - ruler indeed of the roads, passes, towns, and plains, but what can it have meant in the Balkan highlands, or in Greece and Epirus, in the mountains of Crete where the Skafiotes defied, from their hilltops, all authority from the seventeenth century onward, or in the Albanian hills, where, much later, lived 'Ali Pasha Tepedelenli?

The essay is more or less an application of this paragraph to the mountains of Northern Luzon, one whose parts journey horizontally through different ways of understanding mountains and vertically/sinuously between indigenous and colonial applications of that knowledge. Give it a read if that sounds interesting. The essay featured in Longreads’ roundup of the year’s best reported essays, thanks to Anand Gopal, who liked the opening (and whose own reporting has long been awe-inspiring to me, and whose book, No Good Men Among the Living, will surely become a classic).

It’s nice when a darling gets appreciated! More often I regret them but in this case I’m happy we ran the opening, an alienating algebraic equation, as it stands. I find alienation to be one refreshing effect a nonfiction writer can strive for but it’s also one few publications will tolerate. Probably the most common fight I have with editors (not Will!) takes place over moments in my writing where there is risk of alienation, misunderstanding, or confusion. They are moments that require a reader to suspend comprehension or trust. I tend to believe readers are capable of meeting these moments, and I think many writers agree, but it’s not a belief that, when put into action, rewards skimming, a thousand open tabs, or “reading for information,” a mode of engagement with nonfiction we are taught from an early age is distinct from and incompatible with “reading for pleasure.” Editors worry the reader will turn away, and probably some will. But the trust is always a partial fiction, the information always complicated by how and where the writer is situated, and in this sense some alienating friction can be an act of illuminating honesty.

//

As I contemplate a year of creative efforts, I'm reminded of the piece of homespun wisdom a friend of mine often heard in the Kurdish village where he grew up: "A chicken lays eggs--and shits, too."

Here’s everything I published in 2021:

In February I published “Inside Xinjiang’s Prison State,” an interactive feature in The New Yorker about totalitarian systems of control in China’s largest region. The essay follows several men and women navigating the rise of a prison state in their homeland, using illustration, animation, photography, maps, and audio recordings to accompany the text. I wrote about the making of this project for The New Yorker’s newsletter here, and at greater length in my own newsletter here.

In March, Reeducated, the companion piece to “Inside Xinjiang’s Prison State,” and The New Yorker’s first V.R. documentary, premiered at SXSW. I also wrote at great length about the making of this film, here and here, so I won’t say more here. If you subscribe, you know all about it. The film has now appeared at 15 or so film festivals from Taiwan to Venice to Tunisia, and will make a few more appearances in 2022.

I worked on a New Yorker Radio Hour episode, which features some extra reporting from me and more from staff writer Raffi Khatchadourian, and which was broadcast on WNYC. A little behind-the-scenes documentary of my project lives here. All of the above work with The New Yorker represents a good chunk of my pandemic life. But I have also been working on other things, some of which predate Covid-19. Two pieces came out just this past month.

As described above, for the most recent issue of Granta I contributed a piece of travel writing, “The Steepest Places,” about the Cordillera Central range of Northern Luzon.

I also reviewed Sean Roberts’s excellent The War on the Uyghurs for Reason Magazine. My review focused on China’s adoption of the US war on terror model to justify the persecution of ethnic and religious minorities, exploring what I think is the most under-discussed aspect of the ongoing crisis in Xinjiang/East Turkestan.

Two of the best books I read this year were novels by the Polish author Magdalena Tulli: Dreams and Stones and Flaw. They’re like nothing else I’ve read.

In lighter reading, Epitaph for a Spy by Eric Ambler was a perfect summer espionage novel.

In nonfiction, I was consumed by research, much of it not very contemporary. Two older works of scholarship I can recommend to general readers. The first is Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in India by Ranahit Gura, a book that helped launch subaltern studies as an academic subdiscipline and brims with originality. Much of what we think about peasant movements and anti-colonial insurgencies was thought out and interrogated by Guha. (If you like but are skeptical of parts of Hobsbawm’s work on the issue, I highly recommend.)

I also was thrilled by Pasyon and Revolution, a revisionary account of the political and religious origins of the Philippine revolution(s) by Reynaldo Clemena Ileto. The book uncovers incredible lost messianic movements hiding inside the death rattles of the Spanish empire. This book was hard to find but worth the hunt.

Finally, although I missed November’s installment due to travel, I will aim to keep this newsletter running monthly in 2022, using it as a notebook for myself and a bullhorn to advertise my published writing. I’ll also continue to invite friends and collaborators to recommend work.

xo,

Ben